Warren Zanes shares his trip into the past with Bruce Springsteen.

Warren Zanes has written the best book about Bruce Springsteen. His art. His fears. His redemption. Deliver Me from Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Nebraska’ takes the reader from inspiration to execution during a seminal period for one of rock’s icons, while also stripping all the ‘icon’ bullshit out of it. Instead, Zanes concentrates on a man and his guitar in a rented New Jersey ranch chasing a vision of America.

A former member of the early eighties indie rock band the Del Fuegos, an honored professor, and an author of a fine biography on Tom Petty, Zanes once even played with Springsteen as the Boss hopped on stage with his band at some small joint. Interestingly, seeing Springsteen do the same thing in 1981 when he was working on Nebraska, I remember him telling a bunch of us kids in the back of The Stone Pony in Asbury Park that he was cutting songs by himself with a home recorder. What the hell is that? Turns out Springsteen knew as much as we did. He was still learning, experimenting, and making demos, never considering a record, or for anyone beyond management or the E Street Band to even hear it. Zanes reminds us that this is the key to unlocking the raw expression of Nebraska, what I (and Springsteen, too) believe is his finest work.

No one was ever supposed to hear it. That raw honesty is its secret ingredient.

Deliver Me from Nowhere is as uncompromising and introspective as the album it covers, recounting the author’s visit to Springsteen’s current Colt’s Neck, New Jersey residence to comb through the corridors of his psyche, his memory, and method. The two men also visit the humble ranch-style house where it all went down, as Springsteen shares with Zanes the acoustic guitar he used and the infamous painting of his deceased aunt that haunted his childhood and is reflected in the album’s themes.

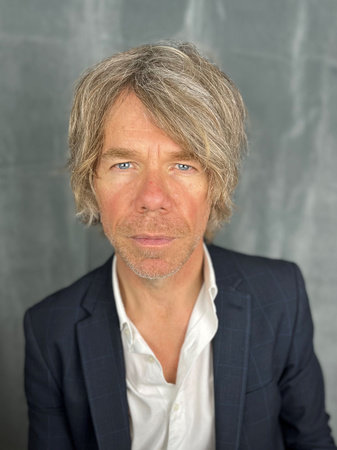

An engaging conversationalist and true fan of his subjects, it is easy to see why first the late, great Tom Petty and now Bruce Springsteen put their trust in Zanes to tell their stories in such an intimate and revealing way. I had the pleasure to sit down with Warren late last month to discuss Deliver Me from Nowhere, as well as his passion and excitement for the album (and its creator) that still resonates.

.

Photo by Piero Zanes

Why Nebraska for you? Why did you feel you needed to write about this record, sit down with Bruce, and get this story out?

I felt some connection, attraction, deep interest in Nebraska, but I wasn’t entirely sure why I felt all of that. I came into this project with a long-term relationship already in place, but I didn’t know what my psychological attachment was to it, and I felt like a book process was going to help me understand that. For one, I didn’t have a complete answer for “Why would an artist at the top of their game, who was poised to go big, go this strange?” You know, The River was Bruce’s first number one record, he had his first top ten single, “Hungry Heart,” and then he makes Nebraska. I just looked at the landscape of artists operating at the level he was operating at and I didn’t see another artist making decisions like that.

The biggest clues came with his memoir, and though Nebraska passes quickly in Born to Run, that road trip that he takes West doesn’t pass quickly. That was where I went, “Wait a second, this happened right after he finished Nebraska?” And it made me think: “Things happen to people… and they make records.” Sometimes they’re lighter experiences, sometimes they’re heavier experiences, but I was sure that Nebraska, on the spectrum of light to heavy, was all the way at the heavy end – and that he described having this breakdown after the fact. I didn’t want to make it a direct causal relationship, but it was hard not to do that. That’s why I wanted to sit in a room with him, and as I expose in the book, I felt like he got as close as possible to say, “I think that’s true.”

The biggest revelation for me was your positing that he never goes back to his former “self” after this – the whole early Springsteen from the first record all the way up to The River has this arc of a character growing up, escaping his parents, his eventual adult disappointments, divorce, lost loves, and then – Bam! – Nebraska is where Springsteen finds this Midwestern, every-man voice that he uses for the rest of his career to explore stories about hidden demons and economic woe. It’s all there, and you point out in the book a very difficult journey to get there. Nebraska is a story of the ways in which an artist moves. I thought you depicted that beautifully in the book.

I don’t want to overstate the value of my background as a writer and record maker in relation to these projects, but I know it’s in there. And I certainly know that I love the psychological ups-and-downs of record makers and songwriters; it’s such an uncomfortable, euphoric, insightful, lost process. It’s all these things. The more obsessive the artist, the more interesting the psychological journey of making records. I think this is where Tom Petty and Bruce Springsteen are part of the same fabric; they really go after records and go after songs. I think they’re two very different men, but I was drawn to the obsessive nature in which they work. The stakes are high for these guys, whether it’s Damn the Torpedoes or Wildflowers or Born to Run or Nebraska.

The secret sauce of this project is you and Springsteen just talking. It’s mesmerizing stuff. Not only were you able to sit with him and have him bring out the guitar that he played on the recordings and discuss the painting of his late aunt that affected him as a boy, but to walk into the room where he recorded Nebraska with him for the first time in four decades.

Yeah, it all started with John Landau (Springsteen’s longtime manager and confidant), who was my first interview. John has his own amazing background, going from working at Rolling Stone to turning the corner into production, which is a pretty rare thing, and then to go from production into managing one of the biggest acts in the history of popular music. When we were done talking, he just said, “Look, I think you might have a book here, so I’m gonna tell Bruce that you’re writing it, and I’m gonna say I had a good time with you, and I think he might also have a good time.” I think that’s exactly what John did. You know, he’s not working with an artist that he can go to and say, “You have to talk to this guy.” That’s just not the relationship, obviously, and then I heard back from John saying, “Bruce is in.”

The cool thing I have to say about John Landau is when he was calling me to say Bruce is in, I felt like he was as excited as I was. He’s got no reason to be excited for Warren Zanes’ book. He’s got a much bigger fish to fry. Those little injections of energy from another person really matter. And for Bruce, he’s an artist who, if he makes the decision to do the interview, believes, “I’m only going to do it if I can be present.” So, when I asked a question, if he had an answer, he gave it to me. If my question led to a question on his part, he pursued it with me. I think you can feel this in the text. I really tried to get it in there.

I liked how you stopped the narrative for a moment and concentrated on your conversations with Bruce – when he brings the guitar out and begins to reminisce. It’s an authentic connection with the artist wherein you begin to understand the guy who made Nebraska.

Yeah, I wanted to have those moments where the reader is me. They can see the picture of his Aunt Virginia, as you mentioned. They see the guitar come out. I wanted them to feel some of what I’m feeling because it’s true, it was mesmerizing to see those objects. They are the story embodied, but they also tell us something about who I’m interviewing. Bruce wanted me to have the tactile experience. He wants the history we’re talking about to vibrate for me as much as he can. Not everybody operates at that level. This book wouldn’t be near the book it is without his involvement.

Now, take me to when you go to the house where he recorded Nebraska. I think I have it right, this was the first time that he was in there since those recordings?

The way it happened was I write the book, I send it to John Landau, John and I talked for 90 minutes, and then he said at the end, “I’m going to send the book to Bruce, but I’m not going to tell him anything about my feelings. I want a cold response out of him, and let’s see if he feels like I did, and I think he will.”

Ok, so you receive approbation from Landau, and he digs it enough to send to Bruce cold. Now, you’re sitting there waiting…

Yeah, the thing that people don’t know about these guys, when I sent the book to John Landau, he called me the next day. He did not take weeks. When he sent it to Bruce, it was a day.

Springsteen got back to you, like, two days later?

When there’s a task at hand, if they choose to do it, it’s fast. It’s really impressive. So, yeah, he got back me and, again, it was really affirming, really validating. Bruce just said, “How can I help you?” And without thinking, I said, “I want to see that house. I can’t find it.” The next day I get a call, and it’s, you know, an unknown number, whatever you see on your phone, and it’s Bruce. He says, “Warren, for the first time in 40 years, I’m standing in the room where I made Nebraska. I spoke with the owner, and he said, I can bring you out here.”

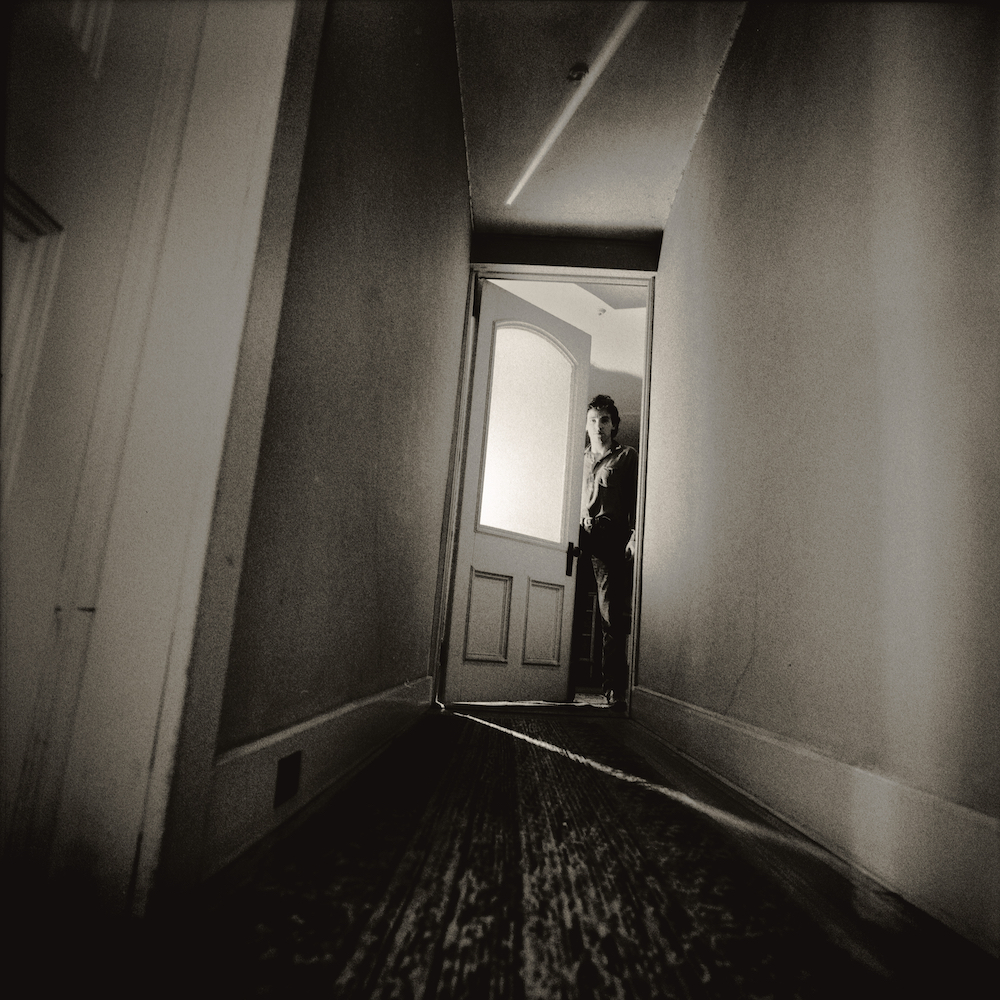

A week later, I go to his house and he takes me out. My first time going into the room was with him. And you know, at the end of the day, I’m a music fan and I know he’s a music fan. I just don’t think you have a career like that without staying close to that part of your identity. That holds for Elton John, Stevie Wonder – I think these people have nurtured the fan within. In that moment, I feel like he’s this hybrid – he’s the artist and he’s a fan in a strange way. I’m 100% fan, of course. I’m walking into this room with the guy who made Nebraska in that room. We’re on the orange shag carpet and it feels like… I think I use the word “pilgrimage” because there’s something spiritual, something mystical about it. I remember visiting High Records in Memphis and knowing that this is where they cut those Al Green records. And it’s like, they weren’t cutting Al Green records when I was there, but it happened there, and that something-happened-there effect is awesome.

I’ve had similar feelings visiting the Hemingway house in Key West or the Mark Twain house in Hartford, and where Dickens wrote and Hunter Thompson wrote, but I didn’t walk in the room with those guys. And it’s not even visiting The Stone Pony, where Springsteen made his bones. This is a room that only Springsteen had been in with an engineer and a four-track recorder to create this masterpiece.

Yeah, I couldn’t even find the house. I couldn’t find an address! You can find most of the houses that Springsteen lived in, rented, and I hope the book doesn’t ruin it for the person renting it now. But, yeah, you’re right. I’d been spending a couple of years writing about something that happened in that room and then I walk into it with the guy who made something happen in that room. Then, after a minute, he handed me his phone and said, “Take my picture.” That was wild.

This was clearly a big deal for him to go back to that place, because, as you discuss in the book, he was not in the best emotional state when he wrote and recorded those songs.

I felt like I was walking into that room with a guy that hadn’t been in it since he was having a very hard time in his life. And he came through that very hard time. I feel like sometimes, for all of us, when we return to the scene where we struggled in life, and we return having done some kind of healing, having experienced some kind of growth, we get to measure then-to-now, and it’s really moving. And being in the room with him was stirring.

Then we get back in his El Camino and go back to his studio where we did the interviews and I could feel Bruce has gone through something with emotional density. I know I felt it at a bodily level. We were both kind of tired. We had tea and talked for an hour, and it was really beautiful closure for me.

I don’t think he would have shown up in the way that he showed up for this book if he didn’t love Nebraska. I think the whole experience of making that record was really special to him.

Does he feel that perhaps the album has been misinterpreted or that it should have had a bigger audience?

I don’t think he’s responding because he feels it’s neglected; I think he’s responding because he feels proud of the record. And he also sees it as a major turning point in his career. Like he said, from that point forward, he was writing songs with almost the mindset of a short story writer, and I think that really mattered with Nebraska. This is why it was important to unpack the influences that he speaks so explicitly about, you know, the Terrence Malick movie (Badlands), Flannery O’Connor, even Robert Frank’s photographs – you need that stuff to understand Nebraska. Most of what he talks about is not musical, and that told me this was like a growth spurt for him. I think for Springsteen, as an artist thinking of himself in relation to fine art, photography, or in relation to film or literature, it expanded his possibilities as a songwriter and performer.

And you have a unique perspective to offer in this book as a songwriter.

As a songwriter, what I get from Bruce is he that he is extremely good at telling stories where each verse can be almost like a contained story with a thematic binding to it. So, he can get a lot done with remarkable economy. That is striking to me. I’m stuck in relationship songs. You know, it’s all ‘me-and-her,’ and the ‘her’ shifts categories. There’s no romance in Nebraska. It’s not love songs, it’s life songs… and it’s not the good life songs, it’s the pain. It is a complete emotional experience without hope, without romance. That’s an interesting achievement to me. But to be fair, the truth is a song like “Highway Patrolman” that goes deep about sibling connection, and we don’t have songs about that, you know?

Two men. Two brothers.

I think part of it is the ridiculousness of how the heterosexual norm is policed. I think homophobia is so prevalent in our culture that even something like the subject of a bond between brothers, you don’t see too much of that, and Bruce does it in such a way that is remarkable. It’s so funny to recall that note he wrote when he sent the demo of the songs to John Landau and how dismissive he is of “Highway Patrolman.” I’m like, “Man, give me one ‘Highway Patrolman’ and I would retire.” It’s so good. So, there’s something about the scope of narrative, and the way in which he compresses it, without it feeling compressed. It reminds me of how much you can do in three minutes. Like how much he delivers in “My Father’s House” about a relationship between a father and a son without the father entering as a character. That’s amazing. There’s a high level of craft that I know he felt once he finished that record and he admitted, “This is my best collection of songs.”

Was there any shift in the author or songwriter in you that started in one place, and then ended up in another with Nebraska?

I think, yes. I mean, I haven’t really been involved in a long-term creative project that hasn’t changed me. And I hope that’s not just because I’ve been lucky with the quality of the projects I’ve been involved with. I hope it’s also because I have an openness and I let the stuff get in deep enough that it can change me. What moved me, to the greatest degree, was that thing about Springsteen and invisibility, the thing we talked about in relation to Homer’s Odyssey, and this idea that sometimes in life you need to be completely anonymous. You can’t have the trappings of ego and success. You go through periods in life where you’re nobody. Let them happen, because it’s almost like the whole of life is the in-breath and the out-breath. It expands. It goes up. It goes down. It builds. It breaks down. Springsteen’s Nebraska, as we’ve talked about, is this period of artistic growth. But he also hit a kind of bottom, and then he reemerges from it. In watching him the way he went through that, and the way he emerged from it, mattered to me. This is a record without any hope in the songs. To me, there’s a lot of hope in the act. He went to a really dark place, he had a breakdown, and with a kind of consciousness, he rebuilt.

Now me, personally, I can’t get too many of those stories. I don’t know why that is, but I really need them, like when I brought Homer’s Odyssey to him and talked about it with him, I was bringing something that mattered deeply to me. I remember finding a book on tape for young adults and playing it for my sons because I think there’s a tremendous amount of human truth in the Odyssey and there are remarkable lessons to learn from it. I feel the same way about what Springsteen did with Nebraska; he hit this kind of bottom, where all the accolades and all the success weren’t fixing him, and he made a record in the middle of that, which is incredible. He didn’t look to career success to make the fix, he went inward, he got some help. He started a rebuilding process before Born in the USA is released, and seeing someone who could easily distract themselves with success choose not to go into the hard part of growing up, that’s powerful to me.

You know, I’m a guy whose father died a couple of years ago and didn’t know him. He lived close to me a few times, but he didn’t reach out. I finally got an address for him and brought my two sons to meet him. They met him once and we never heard from him again. Then he died. And so, in the absence of that kind of parental figure teaching me lessons, the people who have come into my life like Tom Petty did – and I’m doing an extended project with Garth Brooks – but Bruce, the Bruce of Nebraska, I learned something from him in terms of how do you really grow up? It’s not pretty and it’s not a party, and to see these guys do it, and to have a pretty good seat to watch it, or to hear about it after the fact, matters deeply to me.

Maybe I’m open when I go into a project because I’ve got more things to learn, and what I learned most from the book is that even a guy with that kind of success has to get down to the gritty work of finding out what’s wrong inside so that he can do a little work on it and become a better band leader, become a better husband, become a better dad. I think all those stories of hopelessness on Nebraska, he had to go through all those, he had to walk through each of those forests. He ultimately got himself to a place where some internal rebuilding had been done – a higher level of self-understanding had been achieved. And then he comes out with Born in the USA and it’s this massive worldwide hit, and it’s not like his troubles are over, but he’s gone through this human passage that is really deep.

The great thing about your book is you learn that what Springsteen did with Nebraska was not like Roger Waters working through his father’s death in WWII or his growing paranoia about fame on Pink Floyd’s The Wall. As you say, with these short stories, these character-driven vignettes, his sharing of pain is not a blatant single artistic statement, but it’s there. One of my favorite passages in Deliver Me to Nowhere is when Landau gets the demo tape and it’s a revelation, “Holy shit, there’s something deeply wrong with this guy right now.” It’s all there on the vinyl, but it’s not obvious. Someone close to him, like John, can see it. Where an introspective album like John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band is a public acknowledgement of pain, this one is insular, personal, uniquely courageous in its own unique way.

Totally. I think that’s another thing that has made Nebraska last. A couple of messages are, one, you don’t need the commercial recording studio. You don’t need to spend six figures. You don’t need a band. It doesn’t have to sound perfect. It doesn’t have to have perfect tempo, all this stuff. Also, you don’t need to explain it to your listeners… if you trust them. Springsteen had cultivated a deep relationship with his listeners and he trusted them, so he didn’t do interviews. He didn’t write songs that wrapped it all up. He gave us a tremendous amount of work to do and that feels good on our end.

Yes, he goes from spending a year on Born to Run, doing 55 takes of a song, driving Steven Van Zandt to drink, this manic drive for perfection, to Nebraska. The charm of the whole project is that he never meant for it to be heard. He is completely unselfconscious – and you hear that on the vinyl.

Yeah, that’s the crucial point in the book: This is the only official release he made not knowing he was recording an official release. Nebraska is a secret he shared with himself and us.

YOU CAN PURCHASE DELIVER ME FROM NOWHERE HERE!