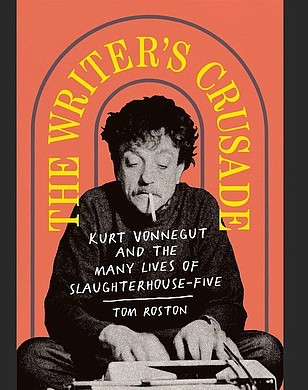

In praise of The Writer’s Crusade: Kurt Vonnegut and the Many Lives of Slaughterhouse–Five and a discussion with its author, Tom Roston.

The most difficult high-wire act for a writer is taking a well-worn and beloved subject and weaving something new and insightful into it. Author Tom Roston has accomplished this with his new book The Writer’s Crusade: Kurt Vonnegut and the Many Lives of Slaughterhouse-Five by getting behind the celebrated novel’s humor, pathos, and charming storytelling that would make the 1969 anti-war, science fiction mind-bender a Twentieth-Century literary classic. For the first time, we meet the many faces and moods of its author, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., who for many, including yours truly, has marked the time of our intellectual and cultural awakening. The best compliment I can offer Mr. Roston is that I have learned why I loved Slaughterhouse-Five or The Children’s Crusade from the moment I cracked it open at 15 and why it keeps speaking to me more than four decades hence.

At the height of the Vietnam War, Slaughterhouse-Five arrived as a mighty yawp from the bow of the counterculture, written by a wise-cracking 46-year-old curmudgeon who had survived one of the most horrifying fire-bombings of World War II as a prisoner of war in 1945. After the devastation of the cultured German town of Dresden, Vonnegut pained to create something of worth from its ashes. And for Roston, and those who adore the book, Slaughterhouse-Five reverberates with mental and emotional trauma, an artistic endeavor to quell its author’s demons, while struggling to fit madness into a logical construct (spoiler alert: Vonnegut never finds any logic in war – “poo-tee-weet” – because it doesn’t exist).

This is where Roston began his journey, oddly spurned on by the whims of weird rumor.

“I knew I wanted to confront PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) in the book because that just seemed like a clear prism through which Slaugherhouse-Five is understood,” Roston shared with me. “But I just didn’t know how I was going to approach it. And then, as you read in the first chapter, what really got me going was when I got wind of this cooky, implausible story that Vonnegut may have committed a war crime.” Roston playfully dubs Vonnegut, Nazi Slayer!, the central figure in a dubious yarn of the young writer and fellow POW searching out their former Nazi guard to enact vengeance upon him. Roston concludes this never happened, but… “It got me energized, and then I started thinking, ‘Why is this relevant?’ And, to me, it was very relevant because it helped address what I felt, and what I feel people feel in general: they’re excited by war, because they don’t understand war. That, to me, is what Slaughterhouse Five is about – trying to explain what war feels like, which is terrible. But a person like me, who has never experienced it, can never really understand that.”

Thus, Roston fills the pages of The Writer’s Crusade with the voices of those who have experienced war (from Vietnam through Iraq and Afghanistan), and moreover, wrote about it in essays, articles, and books, and in one case used painting as an outlet to face living with it. But at the same time, while providing a useful history of how the medical community and the U.S. Army dealt with the soldier’s mental traumas over the years, Roston is careful not to succumb to lazy syllogism. He warns that it is not even certain Vonnegut suffered from PTSD, something the author denied throughout his life, despite bouts of depression, alcoholism, and an inability to connect with people, specifically his family. This is the avatar Vonnegut creates in Billy Pilgrim, a POW, who experiences the same Dresden trauma and the ensuing life of listless inertia, where he becomes “unstuck in time.”

“I discovered Billy Pilgrim to already be insecure and kind of a little bit messed up from the start,” explains Roston. “When he first enters the war, he’s wandering around, letting himself get shot at – he’s lost in it, ridding him of his humanity. War will do that to anyone, and I think that’s what he’s doing.”

And so, one is led to ask, and Roston does so in his book: Is Vonnegut using his protagonist, Pilgrim to work out a delusional construct – being “unstuck in time” and traveling to the planet Tralfamadore to live with a porn star in an id bubble of “happiness” to deal with his trauma. Or are these fantastical things really happening to him? Vonnegut provides clues that these events are indeed figments of Pilgrim’s imagination and merely a coping mechanism, which in turn, gets Roston and readers of Slaughterhouse Five to surmise that its author is using the novel for the same ends.

“No, I don’t think it’s actually happening to Billy Pilgrim, but then that leads us to the ultimate question; does it even matter?” asks Roston, who reasons that if you’re fully delusional, and you think you’re talking to a porn star or to God, and it makes you happy, perhaps that’s okay, by you. “It’s the only bit of happiness poor Billy seems to get,” he concludes.

Roston also deconstructs Vonnegut’s aim to create in Billy Pilgrim a character not unlike Shakespeare’s Hamlet, where there are no ups and downs in his storyline. He is not only living in a fantasy, but also impassive, removed from humanity. “If you drew an emotional line throughout the play, Hamlet just goes straight across. I think if you look at Billy Pilgrim, it’s the exact same thing, it’s just straight across. I mean, in Pilgrim’s mind, maybe things are getting better, but I think Vonnegut’s point was to write a story with a character whose life never gets better.”

Ironically, it was the success of Slaughterhouse-Five that would make Vonnegut’s life better. He was now a famous and wealthy author, and yet, Roston found this to perhaps be the most interesting part of the author’s catharsis. “Before the success of Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut was always trying to merely pay the bills, until he wasn’t, and then once he wasn’t, I don’t know if he was that happy writing, because he wasn’t writing good stuff anymore. So, you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t. I think he may have been the happiest when was working on his masterpiece from 1968 to 1969. Maybe he was feeling everything that he had hoped for an artist to feel, because he knew he had it. I would love to think that. His letters suggest that’s not the case, but his focus during this period created something lasting and great.”

What Roston does not want us to forget, and I could not agree more, is that Slaughterhouse -Five, like Vonnegut’s entire canon, is damn entertaining stuff. It is funny, thought-provoking satire, social commentary with the kind of wit and page-turning drama that made it a best-seller and continues to dazzle readers today. Despite using his work to find light at the end of the tunnel, the author found a relatable voice. I know I related to it as a teenager and still do, as the book has grown along with me into my years as a working writer. I cannot say that about all the books that jazzed me as a kid – and I thank Tom Roston for reminding me of this.

“Almost everyone who I talked to read it in their teens, and they read it the first time as just being a fun, goofy, crazy book,” concludes Roston. “They didn’t read it as being a book about trauma or a book about war or anything, it was just this wild ride.”