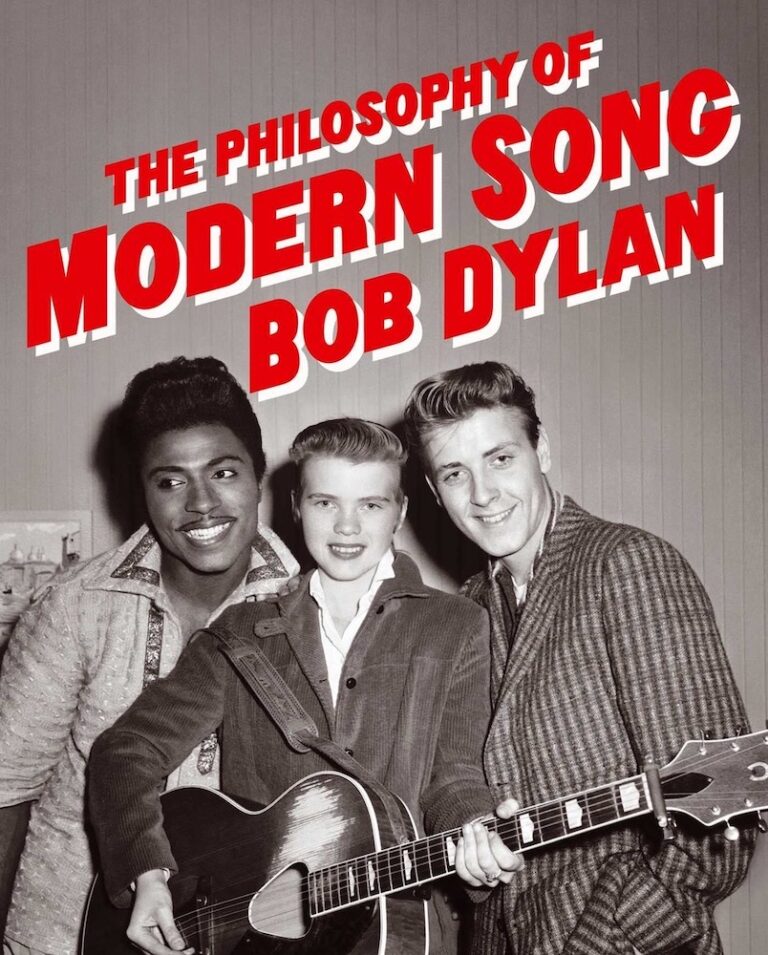

Bob Dylan released the terrific Chronicles, Volume One, in 2004. Eighteen years later, we’ve yet to see part two of this memoir, but as you might have heard, he has just published something else instead: The Philosophy of Modern Song. It’s as engrossing as Chronicles, but it’s also probably the most unconventional book about music since R. Meltzer’s The Aesthetics of Rock, from 1970.

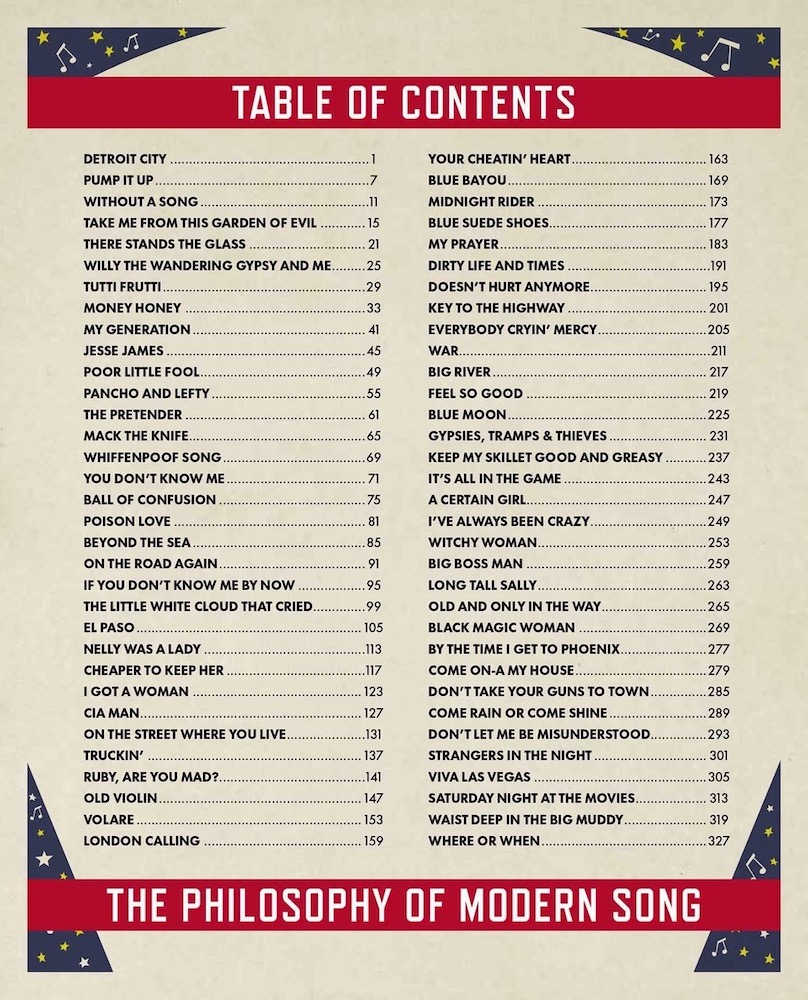

Like that volume, Dylan’s has a title that makes it sound like a textbook. It’s certainly not, nor does it really deliver what the title suggests. Rather, it includes quirky, opinionated essays on 66 songs from multiple genres and decades, some well-known, some obscure – among them Carl Perkins’s “Blue Suede Shoes,” Vic Damone’s “On the Street Where You Live,” the Who’s “My Generation,” Tommy Edwards’s “It’s All in the Game,” and the Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’.” Also: Nina Simone’s “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” Elvis Costello’s “Pump It Up,” Marty Robbins’s “El Paso,” the Allman Brothers’ “Midnight Rider,” Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti,” and the Platters’ “The Great Pretender.” Bobby Darin shows up twice, with “Mack the Knife” and “Beyond the Sea.” So do Elvis Presley, with “Money Honey” and “Viva Las Vegas,” and Johnny Cash, with “Big River” and “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town.”

The mix is as eclectic as the setlists for Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour, and the essays that accompany them sometimes read like extended versions of his song intros on that show. They’re loaded with sardonic humor, wry observations, and mind-bending comparisons such as that Domenico Modugno’s 1958 pop tune “Volare (Nel Blu, Dipinto di Blu)” “could have been one of the first hallucinogenic songs, predating Jefferson Airplane’s ‘White Rabbit’ by at least 10 years.” (Actually, the distance between those two numbers is a bit less than that but the timespan is not the most debatable part of this assertion.) Elsewhere, Dylan proclaims that “bluegrass is the other side of heavy metal…They are the two forms of music that visually and audibly have not changed in decades.” Discussing the Clash’s “London Calling,” meanwhile, he postulates that “the counterpoint to the song is Roger Miller’s ‘England Swings Like a Pendulum Do.’”

Dylan offers a great deal of the sort of trivia with which he peppered Theme Time, reporting for example, that Ross Bagdasarian, who co-wrote Rosemary Clooney’s “Come On-a My House” with author William Saroyan was not only Saroyan’s cousin but the man who provided the speeded-up voices of Alvin and the Chipmunks – not to mention the piano player who lives across from Jimmy Stewart in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window.

Sometimes, these essays find Dylan wandering far from the specifics of the song in question. The essay about “Money Honey,” for instance, mentions the tune only near the end; mostly, Dylan just talks about how “money doesn’t matter. Nor do the things it can buy. Because no matter how many chairs you have, you only have one ass.” Similarly, in a piece on Johnnie Taylor’s “Cheaper to Keep Her,” Dylan notes that the singer “saves you a hefty legal consultation fee by telling you that it’s cheaper to keep her,” but then moves on to a lengthy rant about divorce lawyers, who “destroy families” and “feign innocence with blood on their hands.”

In a discussion of Hank Williams’s “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” meanwhile, he complains that, unlike that number, most of today’s tunes lack nuance and mystery and that “it’s not just songs…everything is niche marketed and overly fussed over.” Before you know it, Dylan is griping that “there isn’t an item on the menu that doesn’t have half a dozen adjectives in front of it…Enjoy your free-range, cumin-infused, cayenne-dusted heirloom reduction. Sometimes it’s just better to have a BLT and be done with it.”

Dylan also bemoans that today’s segmented media makes it easy for people to consume only what they already know and agree with. It’s like letting children pick their own diet, says Dylan: “Inevitably they’ll choose chocolate for every meal and end up undernourished with rotted teeth and weighing 500 pounds.”

Whether he’s off on a tangent or not, Dylan is virtually always colorful. Writing about the Fugs’ “CIA Man,” for example, he observes that buying their records “was like buying some Sun Ra records; you had no idea what you’d get. One record would sound pretty slick – well, as slick as they could sound – but slick as in recorded in a studio with a band that stopped and started at the same time. Then you’d pick up another release and it sounded like it was recorded by a tomato can telephone on the end of a broom handle.”

Even more idiosyncratic than the essays are the meditations – the publisher calls them “dreamlike riffs” – that accompany about half of them. Here, Dylan appears to put himself in the shoes of the songs’ protagonists and imagines a much fuller story than the lyrics provide. In the riff for Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes’ “If You Don’t Know Me by Now,” for example, he writes in part, “You arrive home late…and she wants precise details of where you’ve been, and she’s giving you the business, giving you bad vibes. You try to be cool, but she’s cagey and skeptical. You’re here body and soul, why can’t she get the hang of that. [Dylan seems to almost never use question marks in this book.] You’ve given her everything you can lay your hands on, and she still can’t tune in to you. If she doesn’t know you by now, she must be mindless.”

The book’s more than 100 photographs are as striking as the text. Most are of the performers being discussed or at least relate directly to the song in question, but there are some off-the-wall choices. To accompany a piece on the Osborne Brothers’ “Ruby, Are You Mad?,” a 1956 country single, the book shows Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald as well as Ruby’s mug shot. (Dylan mentions the Texan in his essay, saying, “And then there’s Jack Ruby…you could translate the song any kinda way.”) Though many of the photos are self-explanatory, you’ll likely find yourself wondering who or what some of them depict or when they were taken. There are absolutely no captions, so you’re on your own, like a rolling stone.

Also Noteworthy

Tommy James & the Shondells, 40 Years: The Complete Singles Collection (1966–2006). Whether you own one of the many one-disc Tommy James & the Shondells hits anthologies or the six-CD Celebration: The Complete Roulette Recordings 1966–1973, you may think you have all you’ll ever need from these guys. You may be right, but certain fanatics – you know who you are will also want to pick up 40 Years: The Complete Singles Collection (1966–2006), which first came out in 2008 and is being reissued. This 47-track, two-disc release includes the A-side of “Crimson and Clover,” “I Think We’re Alone Now,” “Ball of Fire,” and all the group’s other hits in their original format – often mono – which is the way fans first heard them on the radio. It also features well over a dozen of James’s latter-day solo singles that the box does not embrace, including a surprisingly good gospel version of “Sweet Cherry Wine,” as well as a rocker called “Long Ponytail” that he recorded in 1962 when he was about 15.

World Party, Egyptology. If you’re not yet acquainted with Karl Wallinger and his great rock band, World Party, you should start with their stellar sophomore release, 1990’s Goodbye Jumbo. But once you’ve digested its infectious Beatles-influenced gems, you’re going to want more. A good next stop would be Egyptology, the group’s fourth album, which came out in 1997, was reissued in 2006, and is now being released again. The latest edition is a remastered two-LP vinyl set that adds live versions of five of the original record’s 15 tracks, all recorded at a New York City concert in 1997. The album’s highlights include the melodic “Beautiful Dream,” a Top 40 British single; the rhythmic, ethereal “Vanity Fair”; and the seductive, piano-based ballad “She’s the One,” which produced a No. 1 U.K. hit for Robbie Williams.

Jeff Burger’s website, byjeffburger.com, contains five decades’ worth of music reviews, interviews, and commentary. His books include Dylan on Dylan: Interviews and Encounters, Lennon on Lennon: Conversations with John Lennon, Leonard Cohen on Leonard Cohen: Interviews and Encounters, and Springsteen on Springsteen: Interviews, Speeches, and Encounters.