Welcome back, guest columnist Seán Barna.

(Barna is a singer-songwriter and activist whose themes run from queer rights and the Trans-Underground, to love and loss and personal experiences. His series of single releases – “Straight Motherfuckers and Their Favorite Friends” (2015) and “Everyone’s Queen on Halloween” (2022), among others like EPs Cutter Street (2014), Cissy (2018), and Margret Thatcher of the Lower East Side (2020) – as well as his latest LP, An Evening at Marci Park, teem with humor and pathos. This is his second guest columnist appearance.)

–jc

People always ask if I get nervous before I have to play a show. No, I do not. Not if there are five people in the audience, not if there are 8,000.

In some ways, I guess you could think, it is a superpower.

***

November 5, 2003:

“Hey, what’s up?”

“Nothing.”

“Alright, are mom or dad there?”

“Yeah.”

***

I wish I had better words to replay and relive. Hell, even the best songs can get tiresome after 20 years living in your head, but all I have is, “Hey, what’s up?” to remember as the last conversation I had with my brother, Kyle.

That conversation happened on a Wednesday. That evening was my first concert with my jazz combo. At the time, I was a freshman in the jazz drum set program at Florida State University College of Music and had been away from home for less than three months.

I have played thousands of concerts since then. That was the last one I gave without the experience of having lived the worst day of my life. My brother was hit by a car on November 8th, 2003 – 20 years ago. The police report listed his time of death as 10:03 p.m. It was a Saturday. I was practicing drum set in room 27 of the HMU music building at Florida State University.

***

My dad asked me, “What’s your plan?”

I’d been home for two weeks. All the people had gone, all the food had been eaten. We had returned to Southwest Florida from our native Connecticut, where we buried my brother.

I had no plan. Somehow, in his own grief, he summoned the wisdom to give me this advice: “Whatever choices you make right now, whether you go back to school or not, or for that matter if you become a drug addict or something, nobody is going to blame you. They will understand. You can do what you want, but I think you should go back to school.”

He was not wrong. Science is pretty clear on this: when a young person loses a sibling, they face an increased risk of early death themselves, for many terrible reasons, including deteriorating mental health from emotional trauma and increased risk of alcohol and drug abuse. Grief is a bitch.

And so, I went back to school. I will forever be grateful to my dad for this advice. Looking back, it is an obvious turning point for me.

As a serious undergraduate music student, your life requires relentless prioritization over four years. You spend countless hours practicing for weekly private lessons and learning or rehearsing music for various ensembles. In my case, I had a weekly hour-long lesson with my drum set professor, Leon Anderson, and was the drummer of one of the university jazz combos. As a jazz major, I was also required to take a half-hour classical percussion lesson – though I voluntarily did an hour-long lesson – and attend the weekly percussion studio class. Then there are multiple music and non-music academic classes.

Knowing I had serious catching up to do on my classwork, I asked my drum set professor if he could just give me a pass for the rest of the semester, since private lessons are basically a class that lasts four years instead of a single semester. “Of course. You have an A.” He also gave me a very nice card signed by everyone in the jazz studio (I wonder if I still have that card? There are some serious names on there…).

also stopped by the office of Dr. John W. Parks, IV. Like me, he was in his first semester at Florida State, except he was the new Professor of Percussion.

“Of course,” he said. “Don’t worry about it. Keep going to your lessons and work on cymbal crashes with Mr. Lloyd or something, but don’t stress about your grade.” (Keith Lloyd was a doctoral student and my graduate student teacher.) “Thanks,” I said.

He stopped me as I was turning to leave. “Oh, and you haven’t performed in studio class yet. On Tuesday morning, let’s have you perform the Bach you’ve been working on for your colleagues.”

My jaw hit the fucking floor. I was furious. Did he not hear what I just said? I do not have the capacity to practice hours a day right now.

Though I had been a semi-professional drum set player since 14 years old, I had just started learning four-mallet marimba a couple months before and could barely read melody. Plus, I did not really know anyone in the percussion studio. I was not one of them. I was a jazz guy, not a classical guy; a drum set guy, not a mallet guy.

And, to my astonishment, none of them knew what had just happened to me aside from Dr. Parks and Mr. Lloyd. Dr. Parks made the choice to let me tell who I wanted, if I wanted.

I walked downstairs to the practice rooms and, fuming, got to work.

Seven a.m. on Tuesday came fast. Dr. Parks chose this time for our weekly class to weed out the students who were not serious about what they were doing. It worked because if you were late by even one second (I don’t mean two seconds and I certainly don’t mean three seconds), the locked door would slam shut in your face. If you did this three times, you failed.

It was my turn to play. I was terrified. Preparation aside, I just was not that good at this instrument yet. J.S. Bach, under the best circumstances and in the hands of the best players, can be a nightmare to remember in live performance.

It started fine but at some point, in the middle, I froze. Unable to remember the next note, I stood there as my vision started to blur from the panic and embarrassment. It felt like an eternity, but of course it was likely four or five seconds. That being said, of all the emotions a person can feel, embarrassment is my least favorite.

Then came one of the most important moments of my entire life.

From the corner of the room, I hear Dr. Parks shout, “A.” Horrified, I strike the A. Then, “F#.” I hit the F#. It continued like this.

With his photographic memory, he could see the music in his head, so he yelled out every single note for the rest of the piece until I made it to the end. Then he stood up and clapped. The rest of the studio, unaware of what was going on, followed his lead and clapped. Dazed, I sat down. I wanted to disappear.

By the end of the semester, I had added Percussion Performance as a second major. By the second semester, I was ranked No. 2 in the studio behind only my graduate student teacher (after a rather stunning amount of practicing over Christmas break). By the end of my first semester in college, I had dropped jazz as a major entirely.

I believe – no, I know – that Dr. John W. Parks did not just save my ass that day. He saved my life. He did not encourage me or ask me to keep going, he insisted.

***

My new routine was practicing eight to 15 hours a day, forgoing all of the things a college student is supposed to do from attending parties to having sex with people you just met. This seemed to be a pretty healthy way to grieve my brother. Better than drinking, right?

Playing the Bach Cello Suite in G Major, or Debussy’s Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum, my tears would fall from my face to the marimba. The music, so beautiful, provided a perfect setting for my sadness.

Sounds peaceful, in a way.

But the reality is this: with even the smallest mistake, I would snap marimba mallets in half. Punch walls. Scream. Or, at my very worst, hurt myself. It was not out of the question that I would pull my hair or scratch my face if I missed even one note. As a percussionist, I wanted to be a bad motherfucker. And I was. But I was also a nightmare to the people around me, especially my best friend then and now, Ben King. What I was doing almost killed me.

During my junior year, my body started to shut down, my hands shaking so uncontrollably in one lesson that Dr. Parks forbade me to practice for a time.

To this day, I do not enjoy playing drums, especially in a rehearsal setting, due to legitimate PTSD and the association between the loss of my brother and the act of playing percussion. I play on all my own records, but I have not seriously practiced since probably May of 2006, but my love and obsession with music did not go away, it just evolved.

On August 18, 2006, I bought an acoustic guitar in Denver before attending a Red Hot Chili Peppers concert alone, hoping to rekindle my love of music.

On August 18, 2007, I saw Counting Crows live for the first time. This is the day I started writing songs. Until I wrote the previous sentence, just this moment, I did not realize this concert was exactly a year after buying my first guitar. Holy shit.

In September of 2014, I released my first EP, Cutter Street.

In August, September, and October of 2021, I toured as a solo artist (with a band) for two months as direct support for Counting Crows, playing for larger crowds than I ever have in my life.

In May of this year, I released my second LP and first on the legendary label, Kill Rock Stars. It’s titled An Evening at Macri Park.

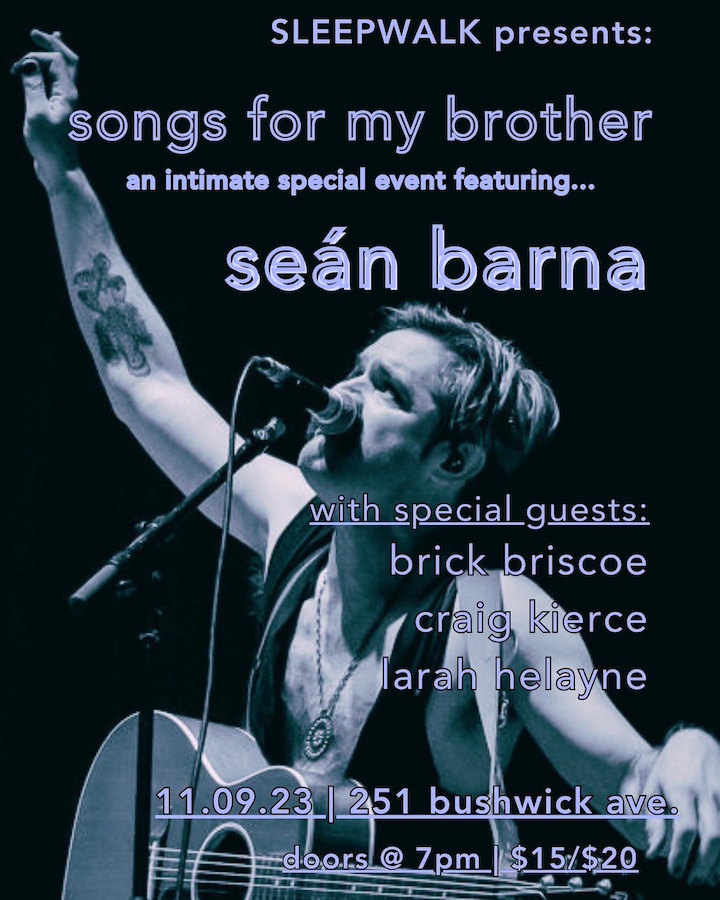

This week, November 9, the day after the 20th anniversary of my brother’s death, I am playing a show at Sleepwalk bar in Brooklyn. The evening is named Songs for my Brother.

It is going to be an emotional, difficult show. I am playing entirely solo. The audience will contain friends and family, including my parents.

What a couple of decades it has been.

***

Am I nervous for Thursday’s show?

No, I am not.

The only thing that scares me about music is the thought of what my life would have been without it. Music is why I am alive, and when I am on stage, I want everyone to know they are not alone.

Be kind to one another.