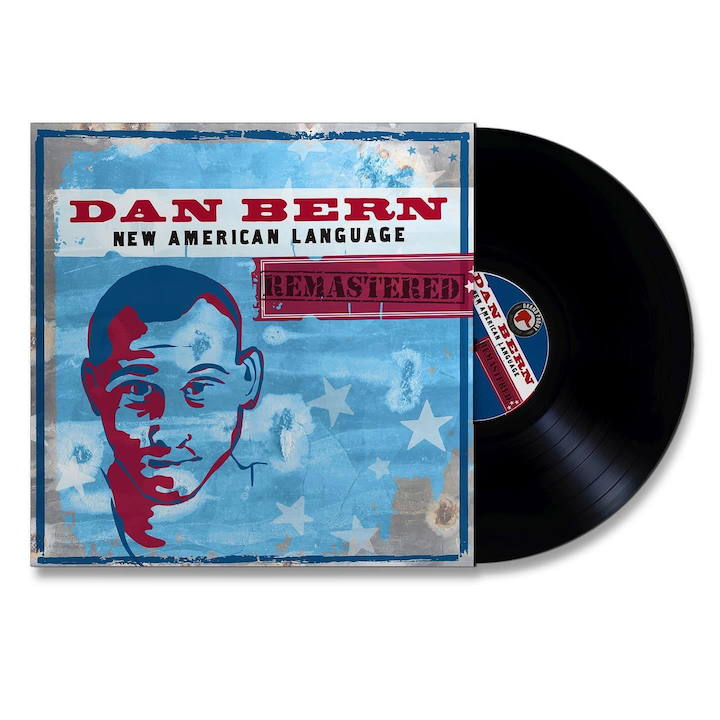

A Dan Bern classic gets a new vinyl release and an abbreviated tour.

This week, Dan Bern and the IJBC celebrate the long-overdue vinyl release of their epic New American Language with a live performance of the album at the East Village’s Mercury Lounge. This is an extremely rare and special event as the longtime singer-songwriter and the unique cadre of musicians that make up what Bern affectionately dubbed the International Jewish Banking Conspiracy over 20 years ago have not played together since the early aughts. Moreover, they have never performed perhaps their finest work live in its entirety before.

Arguably the songwriter’s most lasting, effective, and complete statement of his early career, New American Language is a delightfully hook-laden affair underscored with themes of lost innocence, philosophical conundrums, political awakening, and pop culture asides. Despite defining its times, the album’s messages and infectious grooves remain relevant today. This is due in no small part to the dynamics between Bern’s aphoristic compositions and a genre-elastic, full-throated recording/touring outfit that took his humorously in-depth and poignant songs – many of them perennials to this day like the title track, “God Said No,” “Black Tornado,” “Albuquerque Lullaby” – and set them aflame.

It should be said that I have written about Dan Bern now for over 20 years. Since seeing him crush an opening slot for Ani Difranco at New York’s Carnegie Hall in April of 2002, he has been one of my favorite interviews and, full disclosure, one of my closest and dearest friends. However, before all of that was New American Language, my gateway to what has now reached the 26th year of a remarkably prolific career (over 35 LPs, EPs, live albums, and a bevy of tours both solo and with accompaniment). New American Language was Bern’s third release, a heady arc in a recording artist’s journey. With the debut rush and the sophomore jinx in the rearview, it brings the kind of pressure that can create diamonds or implode creative momentum.

The proof of the former can be found in every track on New American Language – an all-killer-no-filler classic. And now, thanks to Bern’s lovely (and apparently relentless) wife, Danielle, who convinced her husband’s less than enthusiastic feelings about vinyl being “an audio-file’s fetish,” we’re finally getting this masterpiece where it belongs: on record. But what of his reunion with the musicians that made it happen over two decades ago, and what can we expect this week at the Mercury Lounge and the other IJBC dates planned?

A few weeks ago, I sat down with Dan for the first time in a while – too long without an “official” chat for us. I found an emotionally reflective man managing to balance pride and confusion about this incredible album’s staying power and his return to it.

How was reuniting with the IJBC?

It was a moving experience, I gotta say. You know, when the record came out, I was such a crazy person; it might have been a nice thing to just play it through live with the band, but we never did that. So, when I went up to Colorado, they asked me, “What songs are we gonna do?” They were used to the crazy person saying, “Let’s do this new one… da da da,” but I was like, “No, we’re just gonna play the record.” And they said, “Really?” I mean, we might have played any number of these songs over the years – probably at some point we played all of ‘em, but never as a statement. This is more like a movie for me. It felt less like rehearsals than screening a movie, like “Here’s an actual, fully realized statement.”

What was it like to hear those songs again? Did you rediscover something about the album and the guy who made it back then?

I guess, yeah. I think so. It’s hard to describe it, but it was interesting to step into that suit of clothes, to just be buoyed along by the songs, by the arrangements. I even said to the band that it’s bizarre to feel how these arrangements were so perfectly suited to me, and to the way I approach a song, and even to when I would want there to be a break in the lines or a solo here; it’s like somehow somebody at some point figured out the perfect arrangements for this person to do his thing.

How did you guys attack it?

We played at the bass player, Brian Schey’s house for the first couple of nights and then we moved over to drummer Jake Coffin’s little studio, but basically we were just all in a small room sitting in a circle so we could hear each other – no mics even. At first it was, “What order should we do them in?” Well, we already figured that out 20 years ago. “We have the sequence, so let’s play them.” We worked really hard on all of that back then; I remember it took a month or two to sequence it, and so that work was done, now we get to just float through it. And I felt like I was being carried along by the songs and the sequence of them, and I didn’t have to push at all. I’ve done a lot of these songs on my own in the intervening time, but it was illuminating and refreshing to just be an instrument, be my vocals, to just be part of the flow.

Speaking of sequencing, we’ve talked many times over the years of the primacy of the great producer/engineer, Chuck Plotkin (Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen), and how you’ve put together a host of your albums. He helmed this record. How was he crucial to its making?

It’s hard to say. Chuck’s not one of those producers that necessarily gets in there and twist a bunch of knobs, but he was our security blanket. It can be little things, like the rhythmic dimension of the song and recording. If something wasn’t quite working, he could identify it, focus in, and figure how to make it work. I remember with “Albuquerque,” that was one that just needed to float along and couldn’t be too heavy handed, and with the sequencing and just the whole conception as a unified thing, if Chuck walks in [we knew] it was gonna be better by the time he walked out; everybody’s just that little bit more confident that this is working.

We did a lot of work before he was there, though – I mean, months and months of work, but I was also sending him stuff and he was listening to stuff, so he was able to get a feel of what we were doing and give useful feedback. There were at least two trips he made out to Colorado and spent significant time with us, but Will Masisak produced this record as well. He was super hands on and has continued to be even in the remastering of this vinyl release.

Did you play with the band live in the studio? The record has that kind of vibe.

Oh, we did all kinds of things, some of it probably went down as is, but I probably did 50 different vocals over “God Said No” – some inebriated, some at four in the morning. Some of that record, yeah, we probably went “Vroom, let’s lay it down live and the vocal take is the one that was kept.” At this point in my recording process, I’m much more experienced and comfortable with laying down tracks and doing vocals after the fact, but I think at that point it was less so, and I was much more likely to have difficulty singing the vocal after the fact. Will would know better how we did it. His memory for that stuff is amazing.

You have a chance now to be Dan Bern in 2023 singing Dan Bern in 2001. What has that been like for you?

Well, on the one hand, I won’t know until we actually perform them [Laughs]. The first day we got together we were just kind of listening to stuff, getting keys, sort of reacquainting ourselves with them. The second night we actually rehearsed, ran through the whole sequence, and I think I didn’t really depart from the original melodies at all. By the third night, I was looser with them, able to play around with certain melodies, but then when it hit the choruses, or the parts when the other guys would be singing harmonies, I would come back in line. I think that in these intervening years, where hopefully I’ve grown some, I’d just like doing whatever I feel in the moment and it’s your job to follow me, but now I feel like a part of the endeavor and it’s my job to do the part the way it is.

You’re trying to honor the songs.

Yeah, I’m trying to honor it, but also in honoring it, I’m carried along by it. I don’t wanna fight the thing. I guess that’s the same way of saying “honor it,” but it felt like it was alive. It didn’t feel like I was just going through the motions trying to recreate something, it felt like I was giving over to it and it stood up, and once we got there it started to exist in a new way.

Did the other guys feel that way? I know you can’t speak for them, but it must have been really cool for them to breathe new life into these songs they helped create all those years ago.

I think we felt pretty good as a unit. It was interesting, too, because for most of the tracks, Colin [Mahoney], our first drummer, was the drummer, and only at the very end when we did “Sweetness,” which eventually became the first song on the record, did Jake come in, and then Jake ended up touring a lot with us and was the drummer for Fleeting Days, (2003). We’re gonna have both of them at this show and they’ll both find plenty to do.

It’s going to be a big thrill for me to see you perform the whole record, soup to nuts from the cranking “Sweetness” to the elegiac “Thanksgiving Day.”

That’s the plan.

How many of these shows are you doing?

Just three, at least with all of the original guys, but it may lead to some more things with a variety of them. That’s probably the best thing of all about this, at least from my way of thinking. It was quite an undertaking getting everybody in the same place. It might have been better if we had simply decided to do this and then booked a little run of shows specifically, but it didn’t work out that way. I had these bunch of shows anyway and then it’s like, “Well, let’s do it at these places.” So that’s how it’s happening, and I mean, who knows? You gotta start somewhere, so we’re doing this.

It’s tough enough to reconnect with people from your past, but to play with these musicians that meant so much to this seminal music, and just the fact that these guys still play and that they still have their chops, that’s a lot of layers to cover.

That we’re alive, yeah [Laughs]. It was probably stated at the time, but I think we all felt that we had so much fun in the three days when we all convened up there, that everything else with this project is just gravy.

What can fans expect from this show? Will you tell some stories about the songs, about making the record? I feel like it’s set up to be a bit of a memory lane celebration.

Show up and find out! [Laughs] Hard to say exactly, but even when I’m chatty, which sometimes I am, I feel like I don’t really want to give the song away. I’ll set it up, maybe, or you know how in the early Seinfeld shows at the very beginning of each episode he did the standup bit tangentially relating to the storyline, but not giving it away? That tends to be my patter style. If you tell too much about what the song is, then why even play the song? I’m not saying I’m right, because somebody else might do it better, but I’m just gonna, hopefully, let the songs speak. In a way, I don’t want to get in the way of them. Like, “Here’s the record, you have your own relationship with it. This is what it looks and sounds like. This is what it looks like to have this particular bunch of people playing it. This is what it sounds like and have your own experience with us.” I’m gonna try to be in service of that and not get in the way.

That seems to be the m.o. for this entire project, seemingly. You’re part of it, you’re the author of it, but now it’s this thing that’s out there. How do you equate where you were with each of your albums, New American Language as opposed to Fleeting Days or Hoody?

Well, I definitely associate songs with albums.

You do. You like the statement that’s made on an album?

Yeah, for sure. Once they’re on an album, they take on a characteristic for me. I associate the song with time – the time in the world, the time in my life, what was going on. Often, I’ll actually see it in my mind on the page the way it looked when it was written. I know where the page breaks are, and maybe that’s just a function of having had to commit them to memory at some point, but they’re like these player piano roles in your head. That’s why a lot of times, I don’t think I’m alone here at all, like if somebody asks for the second verse of something, then I’ll have to start with the first verse and eventually get to it, and then it’s there. So, when I do a song from a certain album it still retains its album-ness for me. I might do a song and then it’ll trigger another song from that same album.

Right. They belong together, because I know how important you feel about sequencing, as if the songs are taking us through this journey.

Well, here’s the funny thing, because of vinyl restrictions of time…

Right! Was the CD 60 minutes or so long?

Yeah, so the new vinyl version is not Side A / Side B. It’s two records. It’s A, B, C, D. “Thanksgiving Day Parade” has its own side.

A “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” thing. That’s fantastic.

What surprised me about it, going through it and playing it and working through it, was that I think songs six and seven are “Black Tornado” and “Albuquerque Lullaby,” which, I mean, I think any record that has those two songs as track six and seven is pretty good, maybe they should have gone first and last.

But “Sweetness” is such a kick-ass opener. With “New American Language,” “Alaska Highway,” and “God Said No,” that is a murderers’ row right there.

Yeah, but when I was listening to it as I was heading up to Colorado to meet the guys, the one that really got me, where I had this emotional response was probably the last one you would think. You want to guess?

“Tape”?

No.

“Honeydew”?

Yeah.

Why?

I don’t know. I think because it was just really unbridled. Maybe it was because for that one I really needed the band; it wasn’t gonna exist otherwise. I mean, those first seven songs, I think I’ve played those a lot in the ensuing years, but those last five… barely. I think those last five on the record are songs that I needed those guys for. Now they can live again.

Right, and you’re listening to them anew on your way to go see them back in Colorado where it all started. That’s a lot of stuff to unpack.

Yeah, I guess so, but it was nice to unpack it. I wasn’t sure how this whole new vinyl release and getting back with everyone was gonna go, but, like I said, if the only thing this has been for is for us all to get back in the same room and play these songs down, then it’s good.

Do you find that people come up to you and tell you how much they love New American Language more than any of your other albums?

People seem to have had some relationship with it. I mean, yeah, we certainly put a lot into it, and it was a time when everybody involved was able to really focus on it entirely and not have other things going on or distracting us or pulling us apart. I wasn’t writing with anything else in mind other than to figure myself out and communicate it. And, you know, I still play so many songs from it that I feel close to it.

It’s there forever – on tape, on CD, on digital, and now on vinyl. It exists as a piece of work, and it’s good work, man.

Thank you. It’s weird. I don’t know how I’m going to react to this.

Well, you wrote these songs and made this record and now you’re rediscovering it and playing it for the first time in total for an audience, so where do you put this in the great pantheon and things that you’ve done?

I don’t know. I look at all the work as part of something bigger… in total. New American Language is part of that, sure. It’s probably how you feel when you write your books, how they’re received, how you have to live with the results – that’s what I think you do and it’s what I do. So, yeah, I think that maybe the thing that keeps both of us facing it and we keep doing it is the daunting nature of the volume.

FOR MORE INFORMATION & TICKETS TO DAN BERN’S NEW AMERICAN LANGUAGE PERFORMANCE THIS SATURDAY, 1/20, IN NYC, CLICK HERE!