David Duchovny may be the only music artist to have had a song written about him before he composed his first note of music.

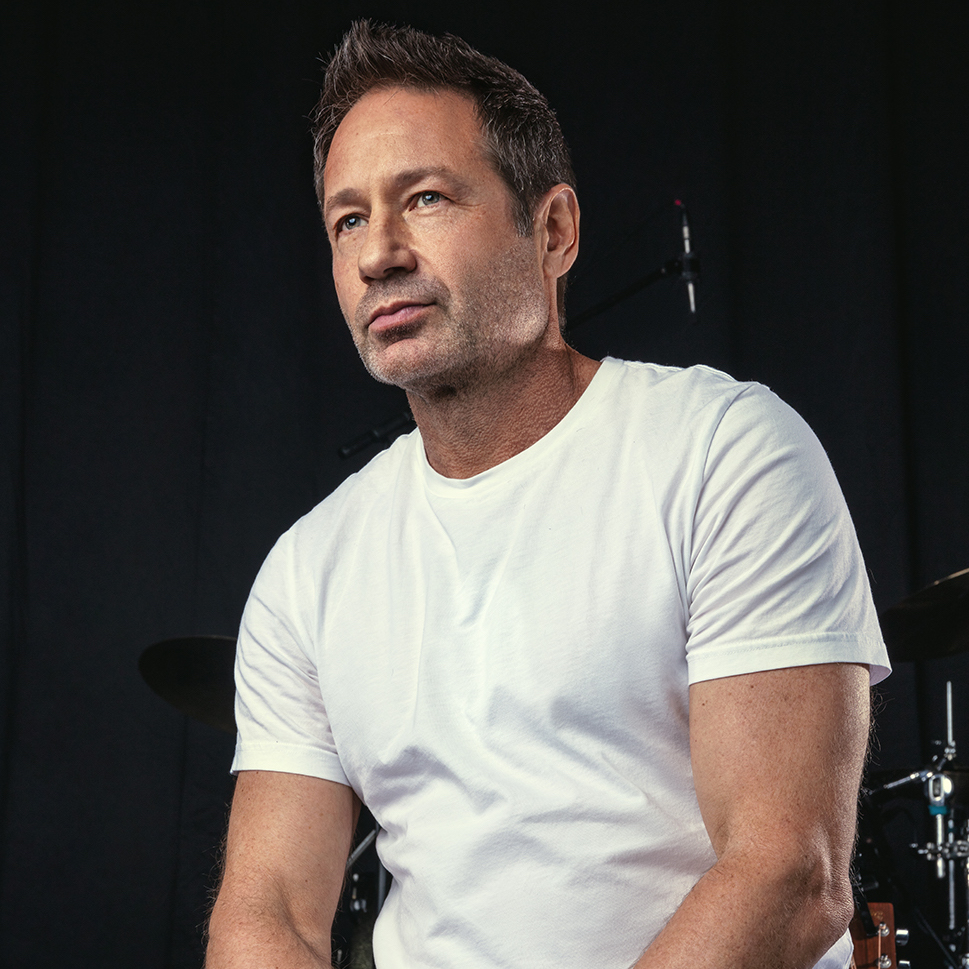

Although he has not abandoned his award-winning career as an actor, director, producer and writer for the screen, both big and small, David Duchovny has taken on a two new challenges: singer-songwriter and novelist. Unlike many of his acting peers, however, Duchovny’s three albums – the latest, Gestureland arrives on August 20 – his music is neither vanity nor novelty, but inspired, eloquent, and poignant. A writer and poet before becoming an actor, his natural talent as both a lyricist and composer and has drawn comparisons to such heavyweights Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, Tom Petty, and Neil Young. He’s also received critical acclaim for his best-selling novels Holy Cow (2015), Bucky F*cking Dent (2017), and Miss Subways (2019). His latest, Truly Like Lightning, an epic adventure that examines how we make sense of right and wrong in a world of extremes, is in developmentat Showtime.

By the way, the song written about him, Bree Sharp’s “David Duchovny (Why Don’t You Love Me?)” was released in 1999 and went on to become an underground hit.

Gestureland was recorded early last year at Outlier Studios in Upstate New York. Then the pandemic struck. After a few months in lockdown, Duchovny and his band (keyboardist Colin Lee, guitarists Keenan O’Meara and Pat McCusker, bassist Mitchell Stewart, and drummer Davis Rowan) reconvened at The Birdhouse in Long Island City, to add overdubs and vocals and refresh some arrangements.

Now Duchovny is itching to get back on the road and perform. “I always get such a kick playing live,” he smiles. “We make each show into a whole evening and take people on a journey. I can’t wait to do a version of [Gestureland on] tour.”

The charismatic, humorous, self-effacing, and engaging Duchovny recently spoke with The Aquarian about his recent endeavors.

Most people are unaware you were a writer and poet in college. Your path to becoming a singer songwriter is similar to Leonard Cohen’s.

And that’s where the similarities end [Laughs]. What I know about Leonard Cohen, which is not a lot, is he started by writing poetry. I saw an amazing video of him accepting an award in Spain where he mentioned he had run into this kid playing guitar in a Montreal park. He said to the kid, “Teach me to play like you.” The kid gave him two lessons, after which Cohen said, “That’s all I needed.”

Why focus on songwriting, performing, and writing novels at this point in your career?

That’s a good question. I don’t know. It was never an option before. I did not begin playing guitar until 10 years ago. I was not a singer. You could still argue that I’m not a singer. It was not like the pieces were in place to say, “This is what I want to do.” It was more like dominos [tumbling in succession]. I wrote a song, which was a surprise to me. I recorded it with a friend, just for me, and then someone came along and said, “You know, this stuff is good, you should turn them into actual songs rather than simple recordings on your phone.”

It was not my focus or my dream, but it was, in a sense, lyrically returning to poetry. Not that lyrics are poems. Lyrics have to make room for the music. In poetry, the words do all of the work. It’s not as if I have all of these poems that I am setting to music.

Billy Joel has said it is nearly impossible to write music to lyrics. He tried once, but the resulting music sounded like a march. The music and melody must come first before the words are in place.

That is true for the bulk I’ve written, but I can also start with an idea or a phrase. Then I will come up with a melody for that phrase. I can start with a few words, a concept, or a turn-a-phrase, such as “Nights Are Harder These Days.” Then I’ll start playing music that fits the way I want those words to feel.

“Nights Are Harder These Days” is Gestureland’s first single – if there are actual singles these days.

It is one of those old traditions that I am attached to. I grew up buying singles – that’s how old I am. I don’t care if it’s considered meaningless. It still feels good to me and I want to see the little 45 of the song.

You’re a few years older than me, but we share an appreciation for those traditions. We have both reached the age where the “check engine” light comes on.

And the “check exhaust” light! [Laughs]

Thematically, how does Gestureland differ from Hell or High Water (ThinkSay, 2015) and Every Third Thought (Westbound Kyd, 2018)?

I’ve had similar concerns throughout the three albums. I write about whatever seems to be floating around me at the time. It’s coming from my point of view, though that point of view might shift from song to song. Part of the fun and glory of songwriting is each song is almost like speaking from a different character in a play.

Conceptually, Hell or High Water had a dark and isolated feel. It had sad, country-ish songs. Every Third Thought was a little more energetic and a little more seventies rock. Gestureland is a combination of the two while stretching things musically. That’s the result of us becoming more of a band. Much better players than me have to execute the music and they were more involved in the music this time. Gestureland is truly a collaboration.

Didn’t you work with the same musicians that contributed to your previous albums?

Yes, I did. For the first album, they were brought to meet me and to make the record. I think they were afraid to step on my toes. At the time, however, I didn’t have any toes, ‘cause I didn’t know what I was doing. So the first album had some beautiful mistakes on it. Good shit can happen when you don’t know what you are doing. They were less tentative during the creation of the second album and a little more collaborative. On [the latest] album they were way more collaborative. There were a couple of songs that originated with them and then I added the lyrics or half of the lyrics and a bit of the melody.

On “Nights Are Harder These Days” your guitarist plays with a Neil Young vibe.

That would be me suggesting to Pat [McCusker] that the riff sounds something like Neil Young, like “Cortez the Killer” from Zuma, one of my favorite songs of all time. Our riff sounded messy and dirty like that. It was the centerpiece of the song.

The recent archival live release Neil Young and Crazy Horse, Way Down in the Rust Bucket includes an amazing version of “Cortez the Killer.”

Talk about three chords and the truth. It’s about feel and hearing what chords sound good together, one after another. There are writers and there are players and sometime they are one and the same, like Neil Young.

The pandemic certainly affected Gestureland’s creation.

We lived with the songs longer and that might have affected the final arrangements. It gave us the chance to engineer and produce the music in a way we hadn’t before. For the song “Holding Patterns,” for instance, we added a synth intro, which we never tried before. When I hear the song played [sequentially] after “Nights Are Harder These Days,” I’m happy for that synth intro. I don’t like jumping from one riff to another. I think that made the album better.

The heavy metal band Anthrax once had a falling out with their singer and dismissed him. This gave them the time to let their songs breathe before reworking and recording them with another singer. The result (Worship Music) was their best album in decades.

Yeah, you never know. I will tell my band to re-record Gestureland with another singer as soon as I get off the phone [Laughs].

Gestureland is musically varied – nut so was your previous record, Every Third Thought, which essentially was an alternative rock record.

Yes. Where I am coming from in my non-musically educated way is just my taste. There is the writing process, but when I want to hear it, I have two things in mind. One, I want the song to be as emotional as I feel it could be and how the production going to service that. Two, I am going to go to sounds that I grew up loving or started to love over time. That is [usually] seventies sound like [Tom] Petty and Neil Young into Wilco. During the eighties I listened to seventies music and during the nineties I listened to Pearl Jam, Nirvana, and Stone Temple Pilots. I have an affinity for that as well as seventies soul, though I don’t have that influence on the album. Naturally, I’m going to gravitate toward sounds that I love and productions that I love.

The nineties bands you mentioned were certainly inspired by ‘70s artists.

That’s a really good point. And that’s what happens when I bring it to my guys who are 20 or 25 years younger than me. Their experience with the seventies was through nineties music. I’ll play them something from the seventies and they’ll say, “That’s great, that sounds like this nineties artist.” It is just a matter of production. The nineties had a different [style of] production.

While growing up. my parents and I did not share the same taste in music. Did you and your parents share a mutual love for seventies rock?

No. My dad was into jazz. Billie Holiday was his North Star and he also loved the swing music of the thirties and forties. I could not stand it. I had my music – The Beatles, The Stones, The Allman Brothers Band, pop and R&B and Motown like The Jackson 5. My dad only knew Bobby Dylan – yes, he called him “Bobby Dylan.” I once played Van Morrison for my dad and he called him a “blues shouter.”

Your lyrics are quite introspective. Given your celebrity, are you not you concerned about revealing too much?

Introspective is different from confessional. What I write about is universal; what we all feel. It is up to poets, singers, and artists to embody that. If the art is good enough, it becomes universal. Someone who knows diddly-squat about me can understand the human condition I sing about. The only way for me to do it is to be introspective. I try to go deep enough so I get beyond my personality. The huge negative side to being me is that I could never try to use any known fact about me or something people think they know about me or my kids. That’s anathema.

You often discuss mortality in your music. As you get older, is that a growing concern?

I guess. I have a strong interest in how the past survives, certainly how people that I’ve lost survive in my mind and I wonder how I will survive after I’m gone. I guess it will be through the things that I’ve done and through my children.

I think about it because I’ve had the privilege of being caught up in a number of fads and I’ve realized just how hollow they were. What deserves to survive? What is surviving in my mind? What has remained that I feel I need to put out there?

Are you concerned about your legacy?

[Worrying about] a legacy is selfish. When you’re dead, who the fuck cares? A legacy is something people who are alive care about. Yes, I don’t want to be a joke, I don’t want to be a punchline, but I can’t control that.

I don’t see you becoming a punchline.

You never know. We have time. [Laughs] And we live in sensitive times.

“Layin’ On The Tracks” has political overtones. Are you concerned about alienating listeners who might not agree with your point of view?

No. There are references in it that make it topical. There is the danger of making it “of a time, ” but I don’t think it will upset people. I can listen to [Lynyrd Skynyrd’s] “Sweet Home Alabama” and disagree with the song’s politics, but I can still love it when it comes on. For me, it doesn’t matter. I don’t vet the artists I enjoy through their politics.

Bringing it back to my [latest] novel, Truly Like Lightning, there are politics in that. There are some anti-Trump references and there are anti-radical left and anti-cancel culture references. It seems like only the people who are more receptive to Trump are outraged. It certainly seems to have spoiled the enjoyment for those readers. I, however, do not relate to that as a reader. If I am reading a book and one of the characters has a political opinion, I take it as part of that fictional world.

Some reader and listeners just cannot separate the author or the singer from the characters they embody.

It becomes that double whammy where people say, “Not only is this actor trying to write music, but he is also trying to be political.”

Does it bother you when people are unable to separate one art you create from another?

Yes, it bothers me. I can only use myself as an example. If you were to put on an actor’s music, I wouldn’t think of it as that actor’s music. I would think of it as music.

There is a difference, however, between some actors, who release vanity projects, and your music which is deep and resonates. Some people are just unable to see the forest for the trees.

The proverbial dust would be me as an actor. When the dust settles, however, the songs will still be there. If you create something that is true to yourself and you see it through, you put it out there. If it is a tree that falls in the forest and no one hears it, that’s okay. The tree is still there, the forest is still there, and someone will eventually find it and say “Oh, this tree must have fallen at some point.” Artists have to be patient. Sadly, we don’t live in a patient world. It’s like the new Neil Young album you just told me about. I am excited to hang up the phone and go listen to it. It’s an album that has been waiting decades for people to listen to it. Art needs to be patient.

GESTURELAND DROPS THIS FRIDAY, AUGUST 20! CHECK OUT davidduchovny.com FOR SOON-TO-BE ANNOUNCED TOUR DATES!