Music is like poetry, and notes are like brush strokes. If you sing something plainly without intonation, without changing the beginning and end of how a word sounds, it’s not poetry. You can say something plainly but if you sing it, it can affect the soul of individuals. In a nutshell, this is how Tony Bennett and one of his instructors would discuss the construction of music and visual art. For Bennett, true art—all art—is about connection, collaboration.

Jazz master, standards veteran, a boss of show tunes, and commander of any other genre his voice has touched—Bennett has been drawing and painting just as long as he’s been singing. Now, he gives a viewinto his life, travels, his native New York City, friends, colleagues, and even a self-portrait (donned in an iconic tracksuit) captured through his personal artwork, on exhibit at New York’s Art Students League (ASL), now on display through January 11.

The Art of Tony Bennett/Anthony Benedetto taps into three elements of the artist’s work. A partial journal, one section features international vistas captured through his years of travel with watercolor sights of Manila Bay in 1981, the South of France, Puerto Rico, the Persian Gulf, Venice, “Roma,” oil on canvas of the white sand beach in Bahia, Brazil, and other moments in time, mostly captured from a hotel window while on tour. There’s a glimpse into how Bennett sees some of his closest friends with hand sketches of Stevie Wonder and Lady Gaga—the pop star at ease, drooped over a piano, hair tousled in a bun, one dangly earring and her long, vampiric fingernails visible. A unique piece done on gouache with Indian ink of John Coltrane and Miles Davis (“Coltrane and Davis”) captures the jazz legends in their element, and one of Bennett’s favorite pieces, “Duke Ellington, God is Love,” which is also part of The Smithsonian Institution’s permanent collection, are a handful of the people who fill in the artist’s circle.

“While you recognize them—since Tony is quite skilled and he does manage to accomplish likeness—the way he accomplishes it is by their personality and approachability rather than the celebrity, which I think is really an accomplishment,” says Genevieve Martin, Director of External affairs at the Art Students League and curator of Bennett’s exhibit, who adds that Bennett captured their likeness mostly by memory. “And it’s demonstrative of how he views the world. These are his peers, cultural producers, and creatives. They’re not just stars.”

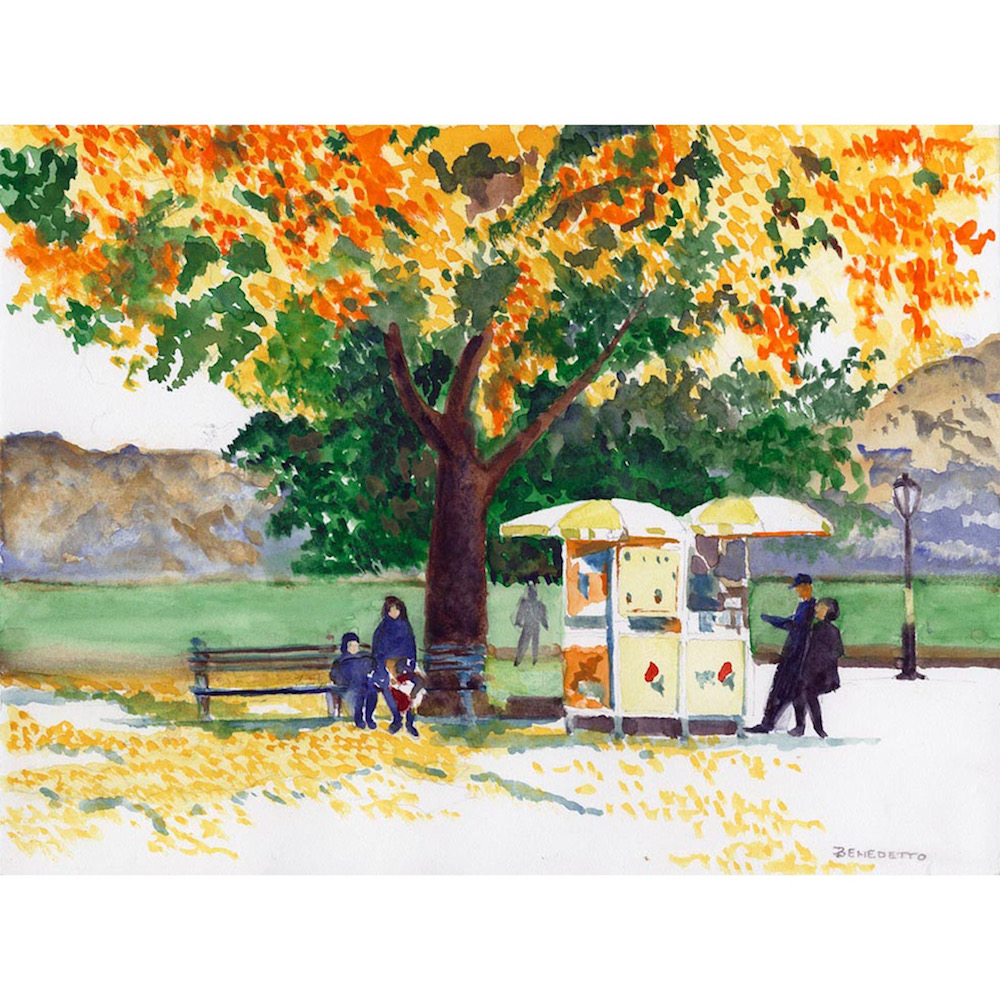

New York City fittingly rounds out the trifecta of Bennett’s work with scenes of The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Statue of Liberty yet center more around Bennett’s home base of Central Park. Part of the permanent collection at The Smithsonian is a simple giclée piece simply called “Central Park,” a vase of flowers overlooking the park aptly called “Still Life Flowers,” and a capture of pedestrians and bikers in “Sunday in Central Park” are some of his quintessential, city scenes.

In all his work, Bennett’s signature is printed simply as Benedetto. Born Anthony Dominick Benedetto in Astoria, Queens on August 3, 1926, Bennett has always used his given name in all of his art. Under the moniker Benedetto Arts, some of his pieces are available for sale (price upon request)—anything from sketches of local jazz and other musicians (i.e. k.d. Lang rehearsing), various still life works, and destination-centric pieces.

He has always continued to sharpen his skills with classes and workshops throughout the years, but one ASL instructor who had a significant impact on his work was Everett Raymond “Ray” Kinstler. In fact, Bennett’s exhibit was conceived in tandem with the ASL introduction of The Everett Raymond Kinstler Lifetime Achievement Award.

Both men attended Manhattan’s High School of Industrial Arts but never knew one another at the time, until a chance meeting more than three decades ago, when Kinstler saw Bennett at an event and called him “Benedetto.” Bennett wondered who would call him by that name, and the two quickly rekindled a deep friendship that would endure until Kinstler’s death this May at the age of 92.

“Over 30 years ago I was at a dinner and a man came up to me and said, ‘Your name is Anthony Benedetto, and you went to the High School of the Industrial Arts, and your birthday is August 3rd, 1926,” Bennett shares with The Aquarian. At first, Bennett was a bit surprised by this but then “Ray” introduced himself and explained that they both studied at the same school at the same time.

“What was most interesting about my first meeting with Everett is what he taught me about art,” adds Bennett. “At the time, when I was applying to high school, I had set myself on attending the High School for the Performing Arts, but I didn’t get in and was always a bit disappointed about that even though I had a wonderful experience at Industrial Arts.”

When they reconnected, Everett told Bennett that he did get accepted to Performing Arts but after his instructor told him to “paint what he felt” on his first day, he packed up his supplies and applied to Industrial Arts. “Everett said he was just 14-years-old and he had no idea what he felt, but he wanted to learn the basic techniques of the visual arts first, which is what they concentrated on at Industrial Arts,” says Bennett. “And that changed my whole outlook around, and we remained close friends until he passed away earlier this year.”

Bennett adds, “It’s the same lesson that Louis Bellson once told me—‘you have to know the rules, before you can break them.’ It was an honor to receive an award named after Everett, as he was a beloved mentor to me and to so many other artists along the way.”

Kinstler, who first started teaching at ASL in 1970, did well for himself after high school. He became a world renowned portrait artist. He painted the official presidential portraits of Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford—both of which hang in the White House today—captured the likeness of artists and actors like Clint Eastwood, Salvador Dali, Carol Burnett, Leonard Bernstein, Katherine Hepburn and, of course, Bennett himself. Before the portraitures, Kinstler’s art stretched into movie posters, forties and fifties western, mystery, and romance pulp art illustrations like “Zorro” and “The Shadow,” in addition to his comic art (“Hawkman”) and worked for publishers like Ziff-Davis Publishing Company, Atlas Comics/Marvel Comics, DC Comics, and Avon Periodicals.

“The way they communicated was through art,” says Martin. “Everett would bring Tony in and work with him. It was almost like improvising with music, like jam sessions.” It seemed logical to ASL that the very first recipient of this award should be Bennett. Yet, it’s still unclear who his other instructors were prior to Kinstler—even though ASL has record of every student dating back to the 1870s—since Bennett attended the school anonymously for many years.

“He has been diligently studying and perfecting his craft, and at his age, how extraordinary is that?” says Martin. “A lifetime achievement in music aside, to then, at this point in his life, still be so curious about the world the way he is, it’s so inspiring.”

For Bennett, now 93, painting just wasn’t enough. When he was well into his eighties, he wanted to learn how to sculpt and tapped into the Art Students League once again. Frank Porcu, sculptor and instructor at ASL for more than 20 years, first met Bennett at a Metropolitan Museum of Art event nearly 10 years ago and soon became his sole sculpting instructor and friend. A New York-bred Italian like Bennett, yet nearly 50 years his junior, Porcu grew up knowing about the singer through family, but never knew he was a trained artist. Porcu taught Bennett how to sculpt in the singer’s Central Park South studio, and the two also formed a close friendship, often going for meals, to museums, and jazz clubs together.

“When he started talking about painting, I was shocked,” says Porcu. “I didn’t expect him to know so much and to be able to hold his own in an artistic realm. I didn’t know he was a painter, so we instantly connected.”

Bennett’s first, finished sculpture was of longtime friend Harry Belafonte. Porcu went on to start work, with the assistance of Bennett, on two busts in the singer’s likeness, including one titled “The Best is Yet to Come”—based off the 1959 standard originally written for Bennett—which depicted the crooner descending the steps with the muses playing music around him.

Their instant connection shows in the finished product. “I don’t think the bust or the work would be what it is without that collaboration,” Porcu says. “To sit down and talk to him and get ideas from the stories that he tells as I’m working, that really fuels me. A song is a collaboration with the writer and the singer, and the audience, but he taught me that sculpting is a collaboration, too.”

Hanging with Bennett, Porcu soon learned that when you step into a room with the man, he literally lights it up. He remembers going to a one jazz club, where Bennett introduced him to a drummer he’s known since his twenties. Porcu was in awe of the musician, who, then in his eighties, still made his own drumsticks by hand. Sitting to lunch near Bennett’s studio at the Ritz Carlton, Porcu noticed people passing by casually taking photos of the singer as they ate. “It’s odd sitting at the table with someone who, no matter where you are, people are walking by taking pictures,” says Porcu. He asked Bennett, “Does this ever bother you?” Bennett replied, “No, it’s my life.”

A huge part of his life has also been ASL. Just blocks away from Central Park South, the Art Students League’s alum measures up to Bennett’s calibre with Mark Rothko, Georgia O’Keefe, Louise Bourgeois, Jackson Pollock, Ai Weiwei, Norman Rockwell, Roy Lichtenstein, among the dozens of locals, celebrities, and other artists who have studied at the center since its inception in 1875. Producer Ric Ocasek of The Cars, who recently passed away this September, and was more of an abstract artist, also tapped into ASL courses.

Not a traditional art school, it was founded by the conception of breaking from the studious norm of the National Academy of Design. The institute doesn’t have a traditional application process. Artists of all levels and disciplines—printmaking, drawing, painting, bronze casting, and welding sculptures—have the freedom to learn and create with affordable classes taught by established artists.

Perhaps this was always the main draw to Bennett, who, to this day still has a deep connection to his hometown. Bennett would always talk about his mom Anna and how important it was growing up watching his seamstress mother work for a penny a dress, remembers Porcu, and how this changed his life. “He’s just so generous and so not what we think as this celebrity….” says Porcu. “‘That’s why he was always involved in breaking from the star-studded world. He’s just an old borough guy, and I really appreciate it.”

In studio, Porcu remembers Bennett would often stand for long periods of time as they worked. In fact, both were feeding off one another’s energy and would work for hours—mostly standing. “Someone would call me and say, ‘Tony was tired, did you ever think about asking him to sit down?’” says Porcu. “I’m an Italian American, and I grew up in a way where you don’t tell your elders to sit down. It’s just disrespectful, and I would never say that to my father or my grandfather. They just have this mentality where they don’t stop, and the day they stop is the day they die.”

Those genes are keeping Bennett going. Last September, he released Love is Here to Stay, a tribute album with longtime friend, Diana Krall, fixed on the music of George and Ira Gershwin. He popped on stage with Billy Joel earlier this year to duet “New York State of Mind,” then packed a sold out Radio City Music Hall for his own show in April.

He’s won Emmy and Grammy awards, among dozens of other accolades, yet was humbled to be recognized at the recent gala as a visual artist. It was an emotional evening on many levels, including a special revelation during a performance by R&B duo Lion Babe, consisting of Jillian Hervey and record producer Lucas Goodman.

Pausing for a moment during her performance, Hervey, who is also an artist and has been taught at ASL from painter Jason Bard Yamosky, stopped to share a story from 19 years earlier. Bennett was on a flight with her mother, Vanessa Williams, who was asleep with Hervey’s newborn sister, Sasha, in her arms at the time. When they landed, Bennett tapped Williams and handed her the sketched pencil drawing of them sleeping, signed “Benedetto” in the corner. “My mom was touched and brought the drawing home and framed it,” Hervey tells The Aquarian. “I always remembered the story, and always love finding out when artists express themselves in different ways.”

Hervey always appreciated knowing that Bennett marched during the Civil Rights Movement and was involved in social justice and commended his artist collaborations. “Being a music lover, I have always appreciated his willingness to collaborate with people from all ages,” says Hervey. “Amy Winehouse was one of my favorite singers, and the fact that he also realized her talents and wasn’t scared to try something new is inspiring.”

When Martin sees Bennett, she doesn’t just see another singer. It’s more than that, so much more.

“There’s an incredible beauty in the fact that into his nineties, he’s continuing to study, and he’s curious and he knows there’s more and has this voracious appetite to grow himself, which is beyond admirable,” says Martin. “He understands how to present his voice, and he looks at art not just as a hobby. Tony doesn’t see art like that.”

An artist in every sense of the word, Bennett is still known to carry his sketch pad around with him. After all, the best is yet to come… and… won’t that be fine?