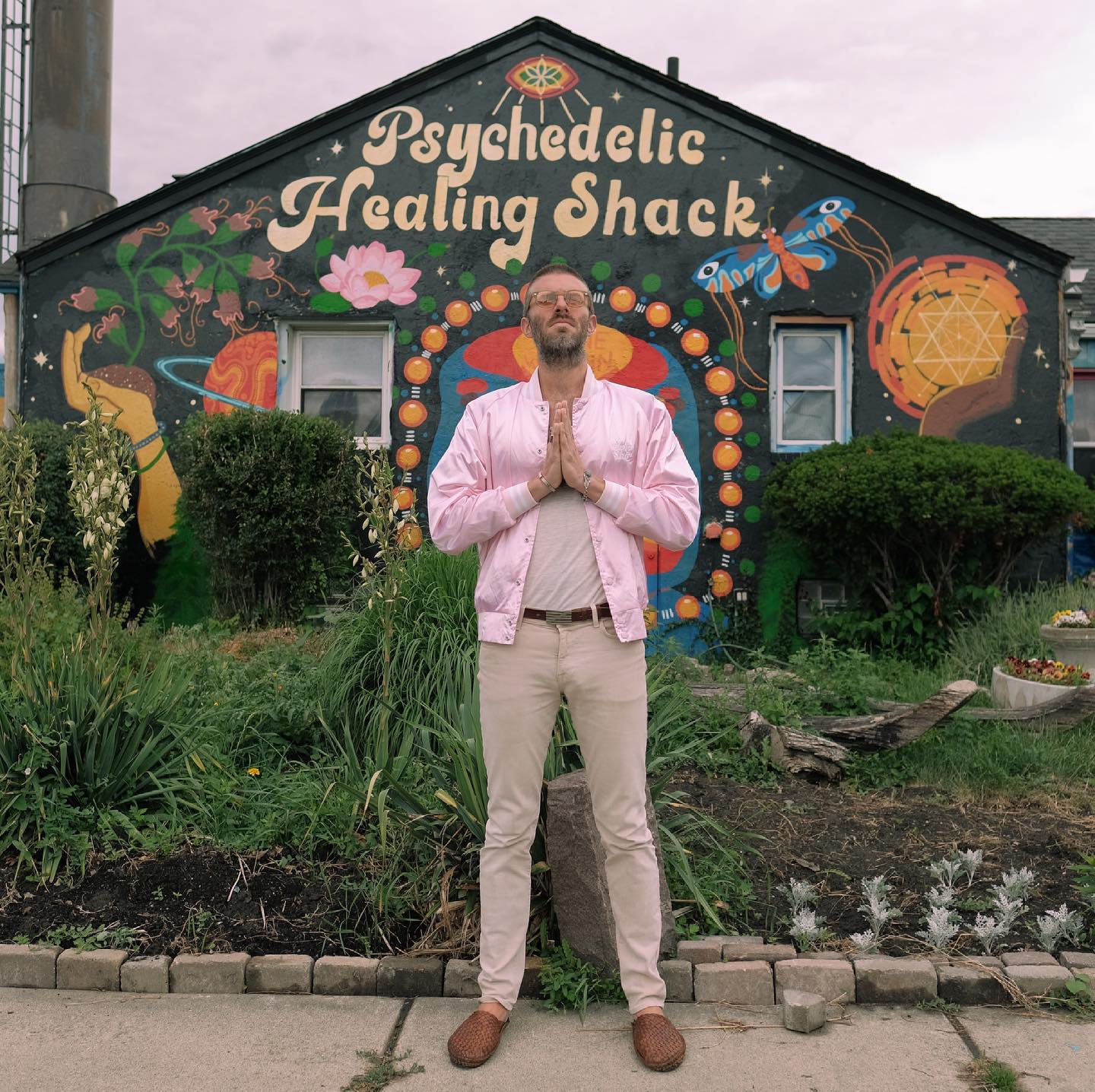

Friendly and charming are an understatement when it comes to Zac Clark, an artist of many words and even more talents. He happily interacts with fans, peers, and the universe at large with whimsy. It’s almost as if he can’t help that his radiant personality trickles into all that he does – including this interview.

The Aquarian had the immense pleasure of having the most mystical conversation with artist/intellectual extraordinaire, Zac Clark. Clark is a young artist, but far from inexperienced. He has played alongside many fellow distinguished musicians, including Andrew McMahon In The Wilderness, and has four full-length LPs to his name.

The fourth, Holy Shit, was released on September 24. The singer-songwriter behind the stunning album gave us a comprehensive recounting of what it’s like to release an indie record out into the wild, as well as the experiences that shape his musical world.

This is my very first artist interview, and what better artist to start with than you, Zac.

Oh my goodness, that’s great! That is so cool! I was so thrilled with your review. I think the thing about this record that blows my mind is that I made this conscious decision, Taylor…. It felt very much like a time when there was so much pressure from one side, or at least inside, to deliver something in this moment of coming out of The Wilderness, so to speak. Then there was also this hilarious lack of pressure when the world shut down, and I was like “I really don’t know if anyone will ever hear this or if there would be a road to play it on,” but my whole intention was that I want this to just be exactly what childhood me would have wanted to make if he had the tools. So to have anyone dig it, like you, in a way that I can tell you feel exactly the same way, it’s really the greatest thrill.

So happy to hear that! I really put my heart and soul into that one. The Aquarian is based in Little Falls, New Jersey. We will be attending your November 4 show at The Stone Pony. Do you share any special connections to New Jersey, and are there any specific elements of Jersey shows that keep you coming back for more?

I can’t wait to be back in Asbury Park. There’s a lot to love, how much time do you got? It’s funny, my answer to that question is going to be very elliptical as many of my answers may be – kind of like an earlier Christopher Nolan movie, where I might start in the middle and end at the beginning in a backward shot. Asbury Park in general, wow. My sister-in-law and her amazing, huge family are from the Wildwood area, so I spent a lot of time at their marina with them. There was this magical moment somewhere along the way where Andrew [McMahon, of Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness] and me and the band played the Shadow of the City festival, Jack Antonoff’s festival, and I think it was the first year. We were scheduled to play, and Andrew and I historically with Wilderness tours, we usually do a radio show, and I think in this case it was some sort of brewery/radio station gig just the two of us. We got an extra night in Asbury Park, which usually means for a couple of dudes like us, it was an extra morning of sourcing the greatest local third wave coffee shop and just wandering town. We ended up at the Transparent Gallery, because I was like, “Yo Andrew, do you know Danny Clinch?” I love his work, and there was his gallery. We rolled in and became instant homies with a couple of amazing women named Tina [Kerekes], and Rachel Ana Dobken, the latter of which is like a great singer-songwriter who I’ve now played a couple of shows with, who plays with Danny Clinch in his blues band. My band and I have played at the gallery as well.

Danny Clinch is a creative staple in Asbury Park, and he had a pop-up art gallery at Sea Hear Now a couple of weeks ago, which we had the pleasure of attending.

Of course he did, I mean, that’s his festival, right? Along with a conglomerate of Asbury Park folks, but he’s the dude. He’s so cool and it was just a wild moment, really integral to the whole ride of the last four years for me. When we finished the Self Titled LP, I reached out to Rachel, the aforementioned fantastic singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, and she brought us up to play a little gallery show on this totally slapped-together, last-minute run around the East Coast that me and my bandmates did with a like a week’s notice in December of 2017. To play with – and for – Danny…. He shot photos for us in front of the Greetings from Asbury Park sign, and we’re like “Dude, we love Pearl Jam, we love all of these artists and these records that you’ve shot the covers of,” so he just became an instant homie – the type of person that I always gravitate towards, which is the consummate host person who loves people and is so overjoyed with what they create; there’s no ego, no worry, no sense of hierarchical ‘who is cool and who’s not’ vibes. It was just like “You guys wanna jam, and maybe like sneak a couple sips of whiskey at two in the afternoon?” and I was like “Yes, that’s exactly what we’d like to do, thank you.”

My answer would have been similar.

Nice! Well, that’s my Jersey! The Stone Pony has always been such a cool venue, such cool folks… and I’m just a fan of the shore. I grew up going to Watch Hill in Rhode Island as a kid, and being close to the Atlantic is really special to me, always, so to wake up in a town where you can walk the beach and that there’s some kind of freaky, trippy, almost psychedelic vibe of yesteryear… it’s just always been a beautiful place for me.”

I want to talk a bit about the album. You released Holy Shit on September 24. There was great anticipation from fans and the record was extremely well received. Could you tell me a little bit about what it feels like to release what is essentially your baby into the world and receive so much love and support back, as an indie artist?

The answer is probably unsurprising, but it’s wild. It’s incredible. It’s almost been so cool and so intuitive, this whole process. There was really never any chance along the way to do anything else than to just press the button for whenever the next song was going to come out, kind of cross our fingers, and make some art. As me and my bandmate, Sam Smith, like to acknowledge at every chance we get: follow that path of least resistance. When Andrew and I were talking – gosh it was, I think, New Years Eve last year – I was at our bandmates Jay and Jessie’s house-sitting for them for a couple months or so in the midst of winter in LA NS I remember chatting with him and, just on a whim, found out we were both putting songs out on the stroke of midnight when 2020 turned to 2021. Half jokingly, as I always do with Andrew and how I always do with my friends whose music I love and whose friendship I cherish, I was like “What’s up, I know you probably got some dates on the books just in case you can get out there, what do you think of having a little ZC Band opening up?” and he was like “Dude, 1,000%.’” We kind of laughed and then said “Well the world might still end, so,” it was one of those things where maybe in 2024 we could go on the road again.

Then, one time Andrew just went ahead and sent me an ad map for the tour with my name on it, and I said “I guess we’re off to the races here, I’ll put the record out and see if we can find the last vinyl manufacturer on Earth that can still manufacture something before the next decade.” It all just fell together, so it’s felt almost unreal. I may quote my bandmate, Sam, in that there were so many ups and so many downs all at once, and the downs were so hilarious because they were connected to such triumphs and ups, that it almost feels like we’ve been living in the afterlife. There’s been moments when I’m just like, “Woah! Is this even real?’ Did we really just do this? Did I really make a record in my house while the world had shut down and just dance alone and make music that fed my soul with no knowledge of whether anyone would ever hear it, regardless of whether they would like it or not, and sell the house and jump into a van and kind of just free fall into nothing as Tom Petty would say?” The answer is obviously yes.

It just feels beautifully bewildering and that’s exactly what I wanted – and exactly what I always wanted since I was a little baby who couldn’t even talk yet who was just drumming and singing nonsense syllables. All I wanted was to be surprised, to understand to some innate level how to translate the noises I was hearing from the world and through my head and through my body into something that I could share with people and give to people. So it feels purer than it’s ever been. The thing that keeps hitting me over and over again is there have been fans that I consider friends at this point, who have recognized me in this record, and there are friends of mine that I’ve known for 20, 25, 30 years who have done the same… my middle school bandmate, aptly named Ben Roque, said to me that this feels like the stuff we were making in the basement when we were 12. That’s the thing for me, to have my buddies go, “I hear you.” That’s the biggest gift for me, and honestly what I now really triumphantly and very confidently say is the goal of making music or making any art or sharing anything is like, I give myself divine permission to totally mess around and make whatever I want to make, that makes me want to dance, that I might give divine permission to others to give themselves that divine permission to do whatever they want. That’s the flavor of this tour and the flavor of this moment: I want everybody on Earth to hear this record. Not because I necessarily want to be known, it’s because I believe in the power of human beings who know what they want and give it to the world. I think that’s what really runs humanity, and what nature wants from us is just to dance and create what we innately want to create.”

That may have been the best way a musician has ever explained, to me, why they do what they do. For those that don’t know, you travel the country in a live-in van, and you share your otherworldly experiences through your music. What did you miss most about traveling while we were on lockdown?

You know, it’s funny, and it sounds a little strange to say, but though I instantly was kind of gutted to know that everything was shut down for a while, I was in this really interesting and weird position where I was a young artist in the grand scheme of things. A small upstart, right? I had nothing on the books at the beginning of 2020, before the lockdown. The only thing in my purview was making the record and to make sure I had something to say after making this announcement with Andrew that I would be taking a step to the side to make my own statement. He was like, “Ok, so now you need to make the statement.” I had a lot of personal support from my booking agent, who is Andrew’s booking agent, but not a lot of understanding of who or what I was, or am, or will be becoming as an artist. Even during and after, there were a lot of people who were like, “Well here is this guy who looks kind of funny, who looks a little like an ancient wizard, and we liked him as a member of this group that we can book, but we don’t really know what to do with this guy as an artist.”

Early in 2020 I responded with, “Well, I’m making a record. I’m writing songs with my best friends – one of whom, in particular, Syd, took me out on my very first tour ever and the drummer on the tour is now my best friend and the drummer on my tour – Sam Smith. That was when I was 18-years-old, so Sad and I wrote “Holy Shit,” and we wrote “Wide Open,” “My My My,” and “Devotion” with our friend Daniel Wright. There were great moments of pure collaboration and creation going on, and frankly, I was a little sad that I wasn’t booked on anything for 2020. I was throwing lines out to old friends who were putting records out and going on tour, but it wasn’t looking like I was going to be on the road. Then, when things shut down, strangely enough I was like, “Phew, well there’s nothing to be ashamed of because nobody’s on the road,” you know what I mean? I felt a little embarrassed that I wasn’t really booked and then I was like “Well, no one’s booked!” All I could do is sit and make music.

I’ll be honest, growing up that was my mode. I was in the basement, I was in my parent’s spare bedroom playing with tapes and, later on, with a little more sophisticated gear that I really didn’t know how to use. But that was my joyful place, and I’ll never forget how a friend of mine named Jasmine from Vermont was hitting me up when I was like 13 or 14 or 15 to say, “Hey, I work at a club called Higher Ground, you should come play, I love your music.” I was like, “I don’t even know what that means, to play at a club.” I had been putting music out since I was like six-years-old and there were a few things on the record that came from tapes I found of myself when I was that little kid that I chopped up and turned it into a weird noise. It’s all embedded in there. By the time I was 10 or 11, I found the ability to share music through MP3.com and these early versions of what our internet, social media, and streaming culture is now. Some of my now best friends and collaborators were from that period of time. It was really funny to have someone reach out in my first teen year and say “You should play a live show” and I could not conceive of it. Therefore, being stuck in my house, and to have it truly be my house with my vibe and my incense and my essential oils flowing through the air, my pictures on the walls, my piano, and my drumset, it kind of felt like home. I know a lot of people who had a really horrible go of it being isolated, but what I wanted from the beginning of it was to ‘lean in’ to the loneliness. I wanted to make that love that I felt I was missing and speak to my love for human connection, my love for love, and my love for intimacy in song, because if it wasn’t there I wasn’t going to worry about it or wish for it… because that sucks to feel! It was in a full-on meditation and psychedelic healing process where I was never really wanting for much. I had coffee, probably a little too much beer, salad materials, I had all my gear, and I was happy as a clam.

You have mentioned on social media that you had lugged the entirety of your studio to your home during the pandemic while working on your latest record. Did you find that this experience was a positive or negative for the process?

What’s funny is that it was a return to form in a lot of ways. I think one of my primary collaborators on this record, who I haven’t had on a record in 15 years or so since we started on Young Volcanoes, was Mike Poorman. I met [him] when I was 17 when he opened a studio in Burlington. He came over right before everything went on lockdown and he and I did what we did 15 years ago. He had me sit at the drumset and get some good sounds. He had me sit at the piano and make sure it sounded how we wanted it to sound. Then we went on lockdown, and then there I was with, honestly, a situation I’d been dying for for the longest time, which was that I wanted to be the guy who had control of pressing record, erasing, re-doing, and just showing up at odd hours after watching a movie and being inspired at one in the morning. A song like “Lean In,” came about when I woke up at 4:30 in the morning and it was in my head. I played it 50 times in a row until 6:30 or so. That is what you hear on the record, a live take of me at 6:30 in the morning with the birds waking up and chirping.

I was always afraid to not relinquish the control of the gear to other people who I thought were pros; the people who I’ve worked with over the years, whom I still look up to with such reverence for their ability to manipulate gear and their ability to play, but I found this freedom in this necessity… in a lot of instances, I sent a couple of tracks later on in the process to my longtime bandmate Joe Ballaro and to my longtime bandmate and tour-mate Marc Walloch who plays with Beck and Company of Thieves, as well as Juliette Lewis and AWOLNATION. I sent them tracks, saying, “Here’s what I’m thinking: I need guitar on this and I want it to be kind of like this,” then I’d have another sip of coffee and I’d have my telecaster on and I’d be like, “Wait, you have a guitar, and you know what you want, try it!” I had never played guitar on a record before, so it was the freakiest thing to be like “Well, you have to now.”

And that’s one of the coolest things about this record.

Well, thank you! I agree from my humble standpoint as the ancient proprietor of the Holy Shit Hotel. It was like, “Wow, just do it like you do it.” Again, that comes back to what I really think is the primary and primal joy of this record: being able to give yourself permission and know that you can do it. I think we’re in a great era for it to be pointed out pretty triumphantly, too. We ought to listen to experts when they tell us that their course of study has indicated that we should do this, that, and the other thing…. I think it’s a great thing to be looking to experts for their expertise, but, man, what a freeing concept and really beautifully ancient human gift to be in possession of this reality of ‘you can do it.’

Whatever you do, if you have a sound that you want to create or you have something that you want to write or you have something that you want to say… the world doesn’t deserve you trying to do it like you think everybody else would want it done. It doesn’t really win. The whole interconnected cosmos doesn’t gain any energy from anyone deferring to anyone else. I’ll be in it, but I want to make sure everybody else does the things because they’re pros. I think we win as humanity, and as a small part of nature at large, if we take a deep breath and recognize and celebrate that it’s within us to do whatever we want.

Were you the sole artist on this record, or did you have some collaborators as you have in the past?

There is one other drummer on the record and that is my dear friend Syd, who on a morning in Ohai after breakfast with his daughters, played a drum loop and we loved it. We were like, “Let’s write a song called ‘Holy Shit’ to this,” and so he’s the other drummer on the record. That glorious, maybe one of my favorite drum tracks I’ve ever heard, let alone had on one of my songs, is by him. Then my dear friend Coley O’Toole who plays in We The Kings now – but we had several bands together since I was very young, as well, one of which was called Smoke Signals – he played bass on “Doin It,” because that was what we love to do. Me and Coley and our bandmate Joe Ballaro in Connecticut would love to just go in a room and go “Here we go. There’s three of us, 33% of this song is written by each of us, no matter how anything happens. Let’s press record and let’s have fun for as long as we’re having fun, and when we’re starting to fall asleep or a baby needs to get put to bed or picked up from preschool, we’re done.” “Doin It” was this moment of that idea: “Let’s all hang out for an hour and make something.” I left with a groove and a dream from my tour with Augustana the fall before and my drives through New Mexico and Arizona through the desert there.

This idea was something I said to Dan Layus from Augustana on that tour. He had said, “So, where are you going tonight, Zac?” and I said “I don’t know, I got more of a feeling than a plan – I’ll let the miles decide.” I just feel grateful that there was a palette to describe this feeling I’ve had over the last couple of years like, ‘hands up, top of the roller coaster, get ready for the drop,’ and be excited to be surprised. Coley and Joe played on the record, Syd played drums on “Holy Shit,” and Joe Bolero… he can play anything and he loves to mess around and send me stuff because he knows I’ll find the part that I like, chop it up, and put it in the songs. That’s him on “My My My,” when the most ultimate guitar riff comes in, but it was part of a 20-minute track of him just jamming to that “My My My” groove and we were like ‘That’s it. That’s the song.”

Beyond that, my uncle sent me digitized home videos of my grandfather’s massive eighties camcorder with hundreds of gigabytes in a DropBox really early in the pandemic. I lost my mom when I was 13 or so, and I had such a spiritual experience watching these videos, being kind of embarrassed as one might be seeing ones unencumbered self, but it was so gorgeous to watch me being pretty much the same me that I’ve always been but without any thought of whether it was cool or not, to see my mom and to hear her talk to me as a little kid. I went straight into the studio with a lot of these songs and put my mom in them. And so, you’ll hear McMahon open up Holy Shit, if you listen to it, you can hear him go “All right, Clark!” He’s also prominently featured shaking a cocktail along with the beat. My mom is also the first voice on the record. She says “Where’s Zachary?” There’s a lot of stuff like that, where I reached out to friends, with a “Hey, I’m not going to play you the song, but here’s the tempo, play something.” That was inspired by David Bowie and Brian Eno as collaborators where they would throw a guitar player in the other room, and they’d be like, “Play on this track,” and they’d say “But I can’t hear it,” and they’d respond with “Yeah, we’re not playing it for you, just play.”

One of the best things about this album is the familial sense of the album, including your mother and Andrew and all of these friends that played on these tracks for you along the way. It’s very special to fans, but also seems to be one of the most special parts for you, as well.

100%. That’s the most special thing to me, too. There’s not a single person on there that I don’t love dearly. Maybe the furthest from my longtime friend and family group on there are two incredible string arrangers and orchestral wizards Austin Hoke and Kristin Weber from Nashville. Austin did the string arrangements, and he and Kristin remotely compiled orchestral pieces for a lot of these songs, and I’ve only known them for a few years, but I love them so dearly and I back them so wholly. Beyond that, it was only best friends and family, actually, but even that isn’t entirely true. There was this guy, Andrew P, and there was a point where I was just so excited about getting found sounds from people that I just threw the call out to the internet and there was this guy who was like, “Hey, I found a pair of scissors that sound really cool and maybe you could put it in a song,” and I put it in “What Better Time.” A guy I never met was using a pair of scissors and that’s part of the beat in “What Better Time.” That was the magic for me, and frankly, it’s the mission statement of the whole thing. Holy Shit to me and the reason why Syd and I wrote that song was that I’d been obsessed with listening to Alan Watts lectures from the fifties, sixties, seventies, and listening to his kind of 20th century Westernized kind of Buddhist zen conversations. We became very enamored with John Cage and his incredible book Silence and both of their embracing of the entirety of our experience in what we make or what we do or what we are. He talks about a latin verb that doesn’t have any real translation to english, but it means ‘sacred and sacrilegious.’ One morning at Syd’s house pre-lockdown, Syd was like, “I think we’ve gotta write ‘Holy Shit,’ since we’ve been having this conversation about how everything that’s beautiful is also kind of disgusting, that life itself is this mess.”

Every mess is magnificent, yo, to quote you.

Oh, 100%. I mean, even not knowing that we were going to be in this massive mess that we still are in, that “Wow, we didn’t ask to be here…” I think that I can speak for every human being. We all showed up naked and screaming, totally surprised and bewildered, and yet there’s such a beauty and such a chance and such luck in that totally impossible chance to be alive. On those days where it seems like nothing is going right, you just have to laugh. The faster you laugh, the less you suffer. You’ll hurt for a second, whether you stub your toe or you smash your head on the doorway, which I’m very prone to at my somewhere between six and seven feet tall stature, and whether it’s something like that or someone calling you and saying “I don’t love you anymore” or someone on the street saying something mean to you, someone honking their car horn at you, it’s like, what are you going to do about it?

The way I see it, the choice is in a world where I don’t believe in most binary presumptions, it’s a binary choice: will you freak out or will you be cool? I believe that every mess we are in is indeed magnificent, because for someone to get mad at me for me going 55 in a 55 in the right lane, and they wanna get around me, I had to live 34 years of life and say yes to the things I said yes to and no to the things I said no to, and even if someone throws a whole steaming pot of coffee on me…I’d be all, “Well, it’s been a beautiful ride to get to this.” How can I be mad?

This sheds a lot of light on your lyricism because your lyrics are often focused on big loves, heartbreak, positivity, hope for the future, existentialism, and the philosophical, with psychedelic musical elements. Your music has always struck me as hope in the key of heartbreak and finding light amid darkness.

Well, that’s Holy Shit – that’s it. I wanted to encapsulate it, you know? I think with Young Volcanoes, I started that record when I was 17 and I was young enough – and so possessed with the notion that I only had one shot to make a first record – that I got pretty obsessed with making it some notion of perfection at the time. It took a long time. I remember sitting in a parking lot when I first got the master of the album and listening through. It really hit me when I listened to my record and I thought, “There’s a lot of loss and there’s a lot of hemming and hawing over what you wish would happen, there’s a lot of sadness and ruminating in the darkness.” Before I even put Young Volcanoes out, I was writing I Am A Guest, and I’d made a pledge to myself that I wasn’t interested in putting more darkness into the world. I grew up on emotional singer songwriters from the sixties and seventies, and then found myself gravitating toward a guy like Andrew McMahon and his early bands, because I was a piano player and so was he, and we were roughly the same age. [When writing my music,] I remember being like, “No dude, only happiness.” When I was about to make I Am A Guest, the songs were kind of there, but I got brutally mugged in the Bay Area. There was a gunshot, there was a pretty gnarly beating of the top of my head with the butt of that gun, and I was on a porch in a pool of blood. I remember everyone in the neighborhood came out of their houses and rallied around me. I went to the hospital and I was totally fine, but I remember saying, “No more sad songs. Dude, you’ve been so sad for so long and you have been dredging these dark parts of your losses and your sadnesses. No more.”

Coming around to Holy Shit, I was heartbroken. I was in love, but it was not a reciprocal love, and it was one of those moments where I wanted to sing about the dissonance here, but I want to remind myself that the love I feel doesn’t need to be tied to someone else, and it certainly doesn’t have to be responded to in kind. Yet, singing about the darkness, bringing that darkness back and acknowledging it, made me find a way to celebrate it and celebrate the good part of it. A love lost is not a love lost, it’s just the object of love is not really the object of love. You are the love. A lot of these songs were dance therapy for me – it was an ability to give myself permission to be sexual, embracing of my very deep excitement to connect with people, and this burgeoning ability to connect and let go of any outcome. I’ve really relished the opportunity to circle it back and say, “You can let the dark in.”

That’s such an incredible realization to come to after such a terrifying experience.

I think that the coming back around has been super important and it’s something that I really want everybody to find a way to acknowledge for themselves. There have been some wildly inspiring experiences with people who are toxically positive. It can be a very scary thing in personal relationships and a very ungenerous and ultimately not helpful perspective to give people through your art or presence – that it all must be positive or that you can will everything to work out in your favor in this weird pseudo-science. Ultimately, though, it is in a very narcissistic and a very self-serving and privileged way. I think it’s important to say, “This is dark,” or “This does suck.” I said it onstage last night and I really think it resonated… I felt so blessed to have it resonate. I said, “I just want you guys to know, this is a fucking mess that we’re in, but we’re in it together. We are Holy Shit. We are it. We are the mess and we are magnificent.”

So, this record really was spawned from your experiences over the past couple of years.

It’s been a reflection of the past 34 years, for me, and I feel like I’m one again. It’s pretty amazing. It’s important for me to acknowledge that you mentioned the psychedelic nature of the record, and a few of the songs in particular, such as “How Wild Are We” and “Holy Shit.” Those came from these very beautiful doctor-prescribed experiences with psilocybin. These deep dives into a total break from the rational, intellectual human mind and to tap into what I think a lot of people call the “reptilian mind,” the part of our brain that is instinct and feeling and intuition. I’ve started writing the next record, started recording it already, and that is a further reflection of these moments where I’ll have a notebook next to me during these experiences. To put a notebook and a pen next to you when you cannot even see because you have a blindfold on and you’re in total communion with these plants that have changed your chemistry for this ultimately fairly brief moment in time, to do some automatic writing and translate the experience, is everything. I know it might sound a little wild for some people, but there are presences that kind of narrated these songs for me. “How Wild Are We” I wrote entirely under the spell of mushrooms on a rainy Nashville afternoon. It was just a notebook full of scribbles that said, “Through every mile in me, how wild are we? I see all the world in you.” The whole song was there – all I had to do was put it in order.

Those experiences for me, the value of letting go of your conscious mind and just being whoever the greater expression of existence wishes you to be as part of it, that’s been the biggest thing for me in my writing. The ability to exist and not worry about what other people might think… it has totally blown my mind and dropped me into this state where, frankly, I don’t feel like I can be fucked with.

“How Wild Are We” was declared a fan-favorite pretty much the day your record was out.

It’s a wild thing – to sing that song live. It might be one of my top songs on the record as far as the ones I love. It was definitely the first song I was playing for people when I thought maybe I was making a record. My co-producer on the self-titled record told me the other day that when he listened to the test-press of the vinyl, he said, “That moment floored me. That’s when I knew you didn’t need me and I knew that you knew what you wanted. I was so proud of you and excited for you.” He encouraged me to investigate that reality, that if you’re clinging to something because it offers you some semblance of certainty, if you know you want something else, you better recognize as fast as you can that there is no certainty anywhere. As Jim Carrey said in his brilliant film Jim and Andy, “You can fail at what you don’t want to do, so what do you want to do?”

What made you come to the decision not to make “How Wild” a single?

It’s funny, because the mechanism of putting this record out was really homespun. I would say all along that was the single for the record and as such we wanted to build to it. Looking back, maybe it would have been a spectacular moment to follow “Holy Shit” with “How Wild,” to go instantly into the next song that was a favorite of mine or felt like the big song. There’s a lot of intention behind it and really funny flights of fancy. My primary collaborator, and ultimately one of my best friends on earth, Sam, was like, “‘How Wild’ is a set closer” or “‘How Wild’ is meant to be played to thousands of people, everyone singing the ‘oohs’ in a stadium.” We always had that idea, but there’s no mechanism other than us putting these songs on Spotify or iTunes and me buying a thousand copies of a record. All of us just randomly decided to write, design, compile, and lay out a 112 page book to come with the record. It’s all us, and it’s really funny, because living in Nashville and living amongst the super young artists and super well connected artists who are connected with the right people, we don’t have that.

I can see the back end of Spotify and I can tell you with certainty that it is nothing other than real fans listening to my catalog from my catalog… when it hits, when the right person gets to this [music] and it hits them and they can boost the signal, we will know that it came from family, faces, and names that I know from years on the road, who have hugged me and said “Your music has brought me through something.” [When they have] connected with my music as a mode of survival, I can go, “Yeah, this shit is real, baby.” There’s no bullshit about it, there’s no one listening to this record because they heard it was cool to like this record. It’s people who dig the vibe and that’s a strong pillar for me. I’ve never felt more comfortable, confident, and blessed to have a small, but mighty presence of real people who I know and I recognize and that I love, loving it.”

You’re so open and kind to your fans, always responsive and expressing your gratitude for your listeners. You even went so far as to provide a phone number for fans to text you at. It’s beautiful.

It’s incredible. People I’ve met in the literal middle of the night and had beautiful conversations with, who do incredible things, have reached out and been like, “I don’t know if this is your real phone number, and I don’t think you’ll remember, but this is so and so from so and so. I saw this number and I just wanted to reach out and see if we can reconnect.” There are people who have been like, “I heard you’re playing shows in backyards and on peoples’ roofs, and maybe you can come to my house?” Real people have reached out and said “I want to give you money to continue to make the music that helps me get through my day,” and “come make a moment of magic with me and my family that will help you keep making the next record.” It’s all above board and very simple like that. I’m blown away and bewildered in the most beautiful way to have that direct line of connection and I’ll never not want it. I will always be available to the extent that I am right now to the people that I know and feel love from, because ultimately, it’s very important to me that people know that I am thrilled to be on tour with AMITW, that I’ve been in the band for upwards of ten years, and now I am reverting to my original form – the biggest fan of Andrew McMahon that ever walked the land. He’s a huge fan of mine, too, and we are fans.

That’s the thing that I think people don’t know about some of their favorite artists that they might look up to because of the mechanism of celebrity culture and what has changed about music over the centuries. It used to be that there were no musicians, because everybody in the community was music. Music was embedded in everything we did, it was chanting your way through laundry, and hunting and gathering, and birth and death, and the harvest, and no one was any better than anyone else at it because it was just a function of existence. Now, we have this weird sense that some people can do it and others can’t. We’re all fans. We stand backstage, I stand next to Andrew and watch Annika Bennett who is so young and so new to the road, we just played her sixth show ever. But we watch her, and we love her, not like “Oh, that’s somebody that’s on tour with us,” but someone that we are like “Yo, innately she loves melody, she lives in melody, she comes from melody.”

Speaking of Annika Bennett, when we were talking the other night, I asked “What’s your goal, what’s your dream?” I ask that question to anybody these days. If it were all up to you and you could do exactly what you want to do, what is it? She was saying “You know, I just want to write with people I’m a fan of, I want to write my own records, and I want to tour and do what I love,” and I was like, “There you go.” It’s been a mixture of intention and great luck that I’m starting to get to the point where I gratefully don’t have room to do anything else, but work with people whom I love and cherish and share their innate interest and love for music and melody and philosophy and the matters of existence, and that I love as people. These are people whom I love their kids and partners. I celebrate their presence in the world and I hope that it’s embedded in the music to the point where people who don’t make music feel a sense of permission to say ‘no’ to an experience that is only about money or opportunity and leave space for saying an absolute ‘hell yes’ to an experience that has no guarantee of success, but has a guarantee of innate success in that you get to be with someone that you love and look up to. It’s those moments that you can say, “Wow, you’re an incredible person, your vibe is so right for who you are, let’s celebrate it, let’s record it, and let’s give it to people and see how they like it.”

I think that’s a big part of why people flock to indie music these days, everyone is looking for that special connection that you’re describing so well and translates so well through your music.

I’m fond of saying that as the ceiling rises, so does the floor. If you want your vision to be wildly and widely disseminated and received, you want your vision to be big and you want its reception to be wide and massive. Your output and your investment in it is going to grow as your return grows. I look up to Weezer or Panic! At The Disco or Billy Joel – these people that we’ve played with who do massive things. If it’s that big, it costs a lot more, and the return is probably only marginally bigger or better than when the ceiling is a little lower and the room’s only got 200, 500, 1000 people in it as opposed to 70,000. Frankly, being able to know everybody at the party is so thrilling to me… it’s so joyful to know that I’m going to play on a rooftop tonight in Seattle. I’m so thrilled because it’s so intimate and so vulnerable, and ultimately, it’s a party. I think we all ought to recognize that every day when we wake up, there are limitless, infinite possibilities, and the only thing that limits them is these deep grooves of thinking and expecting and wishing that are kind of ingrained in us from our early youth.

Something that blew my mind, the night I flew back from what ended up being the last writing sessions for Holy Shit – I flew back March 2 of 2020 from LA to Nashville – and I landed in the middle of what eventually became a tornado that tore my neighborhood down except for my house apparently, and I woke up to 250 texts from people asking if I was alright. My tech, Alex Perkins, was in my driveway, because Mike Poorman and his wife who were not in town were horrified as to whether my house had gone down or whether I knew what was going on. I flew in and took my headphones out and in front of me was a magician talking to a kid who had gotten a random upgrade to first class, and he’s telling this kid that, culturally, we think that we have an imagination when you’re a kid, and you don’t when you’re an adult. It’s not true, you have the same imaginative capabilities as an adult, but instead of imagining wild things that you want, that you innately feel are gifts to you and gifts to the world, you’re dancing or singing or laughing – just the pure indescribable and totally non verbal and non-linear joy of being, turns into an imaginative force of worry and wishing for what’s not there.

I think that’s the thing for me these days. I think we all have the capacity to wake up every morning, take a deep breath, and let the thoughts flow by you and let the worries go… let them flow by and then sit there and recognize that they’re all fiction. It hasn’t happened yet, so why not just go, “This is gonna be the best day ever and I’m gonna make magic and I’m gonna meet somebody who blows my mind, and I’m gonna blow their mind.” The world’s going to keep on growing and getting weirder, and the shitty shit might get shittier, and the amazing shit might get more amazing. It doesn’t help any of us to dwell, you know?

YOU CAN CATCH ZAC CLARK OPEN FOR ANDREW MCMAHON IN THE WILDERNESS AT THE STONE PONY ON NOVEMBER 4. FOR TICKETS AND DETAILS, CLICK HERE!